Defiance: Seeing Red - Mark Rothko & Suspiria

Suspiria is a no-surprises murder mystery that dabbles in feminist ideas, tracks the occult, and exists as an adjacent precursor to the slashers of the 80s. The cult classic is beloved for its terrible overdubbed dialogue and iconic for its use of color. The reds, yellows, and blues of this film are so paramount, so specific and intriguing, that viewers can easily bypass the rest of the movie altogether; this is important because in a lot of ways, it’s not a great film. This is the first of a three-part series on the colors of Suspiria.

Directed by Dario Argento and released in 1977, Suspiria follows protagonist Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), a young American ballerina who moves to Germany to study at a prestigious school of dance. The film takes a lot of risks in the strange camera angles that shift perspective randomly in a scene, as well as in the childlike script that is both blunt and sometimes boring. But it is precisely in this unpolished strangeness that we find a truly remarkable film. What Argento lacks in typical movie necessity, he thrives in the subversive means behind storytelling. Suspiria is a courageous film that forces the viewer to engage with color and atmosphere, suspending us in a delirious state that perfectly encapsulates both the plot and the characters. Viewers are immersed, wherein light and color bleed into our peripheral vision, encompassing our entire experience of the film.

You might enjoy this series more if you have watched the film first. Spoilers ahead!

Suspiria opens with Suzy at the airport, having just arrived in Germany. Argento immediately sets the stage for color with a particular focus on blue, yellow, and red objects in the scene. It is pouring outside, and Suzy’s calling for a taxi. From inside the cab, we see showers of rain tinged in red light that splash over the windows, mimicking the blood spray of a classic slasher film. Suzy’s driver takes her through the city, a dark forest, and finally to the front door of the academy—an alluring bright red palace. Outside we see a young woman screaming incoherently, marking the beginning of our mystery. A few scenes later, we see the young woman fleeing the school. She takes refuge at a friend’s apartment—a grandiose Art Deco-styled building of orange-red walls and teal doors. There is a massive stained-glass window with rectangles of bright yellow, red, and blue on the ceiling nearly eight floors up. Not long after her arrival, the woman is attacked by whomever she was fleeing. She is then stabbed and hanged, crashing through the stained-glass window into the middle of the massive red patterned foyer. The broken window pieces impale her friend, who lies in a pool of blood just beside her. The whole sequence is extremely brutal, and an ambitious way to open a film where we have yet to learn anything about our protagonist or the plot. We’ve barely dug into our popcorn and we’re already knee-deep in gore, surrounded on all sides by a red maze room soaked in blood. And yet, it doesn’t land more than a good laugh. What should be terrifying ends up feeling kind of silly. The scenes leading up to the murders require a lot of patience. There’s bizarre drawn-out dialogue, as well as extremely long hovering shots on empty windows and the architecture. It’s meant to build suspense, but the timing is all wrong and nothing adds up. The blood and prosthetics are so profoundly unrealistic that it becomes ridiculous. Taking all of this into account, we also don’t have any relationship with the dead characters yet, and we don’t know their importance within the story.

Suspiria has long been criticized for its ridiculous fake blood, specifically its hue. It is uncanny; too bright, too fake, too orange, too thin. However, it is here, in our entrance to the story, that Argento makes an interesting (and essential) pivot away from the slasher genre and typical giallo mystery. For all of the body horror present in this film (and there is quite a lot of it), Argento’s use of the color red suggests that we’re not meant to be thinking about the body. Instead, he seems to ask us to feel the experience of the color itself.

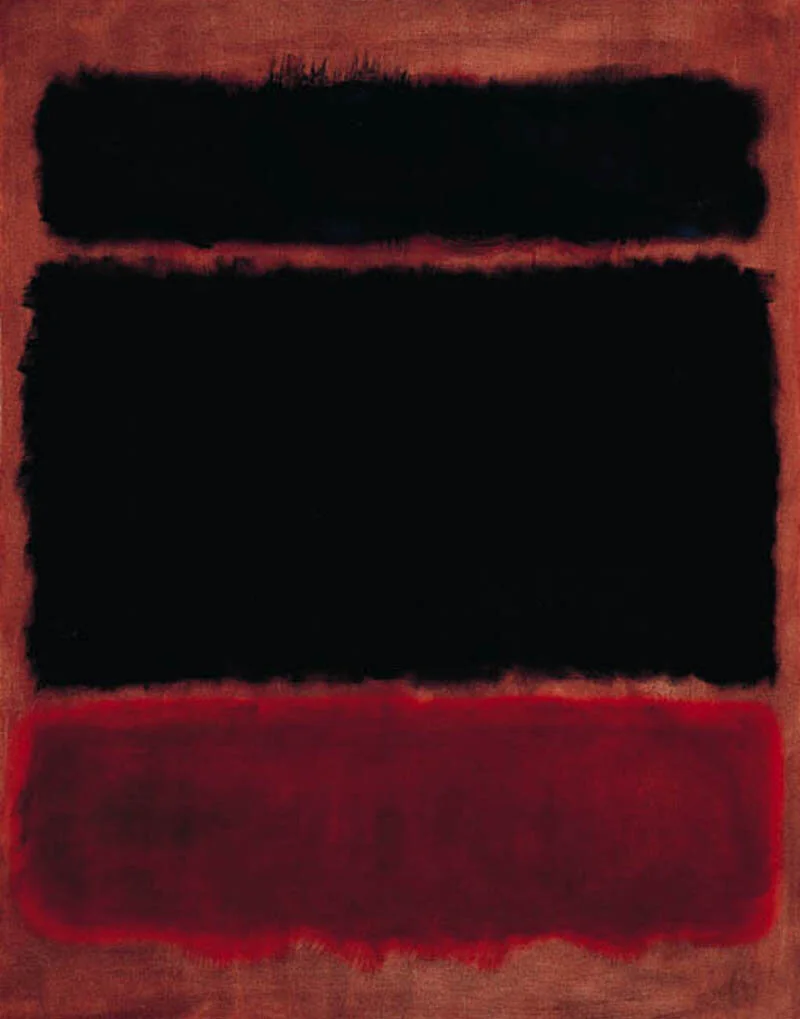

Argento was not alone in his ideas about color. Just a few years prior to Suspiria’s release, the American painter Mark Rothko broke ground with his most famous works, called the Color Fields. The paintings are huge, named for exactly what they are: massive fields of pure color, and when you step close to them, it is the only thing you can see. They are abstract pieces that feature nothing other than imprecise rectangular blocks of uncanny palette choices and odd proportions. Rothko took care to paint with rags in order to eliminate brushstrokes, and he often painted with many translucent underlayers of color to illuminate the canvas. These highly controversial pieces are still criticized today by those who do not wish to engage with the paintings as Rothko intended. When you experience a Color Field, your peripheral vision is drowned in the way the canvas so beautifully captures light under layers and layers of pigment. Imagine staring at a neon sheet of paper for a while and then looking up, except you are already looking up and the colors aren’t neon—they’re more like laughter, fear, joy, despair. And because of this, the paintings are downright terrifying.

According to the Museum of Modern Art,

[ “Mark Rothko sought to make paintings that would bring people to tears. ‘I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,’ he declared.” ]

Black in Deep Red, Mark Rothko

The engulfing sensation brought on by the compulsory act of looking at color and only color is Rothko’s intention—to ask the viewer to feel rather than see, to make meaning from the experience alone. For Argento, the story is not told through dialogue. It is not told through a plot twist or a difficult mystery either. Suspiria is told through experiencing color in three parts: red, yellow, blue. His focus on hue, shape, and atmosphere rather than traditional modes of storytelling push past the typical giallo film into a much deeper level of feeling.

It is important to note that Mark Rothko was a defiant painter. To the modern eye, it may not seem so drastic, but never before had an artist so purposefully rejected the rules of painting. Even other abstract painters had not completely done away with figure and form in some sense. To paint voids was so groundbreaking that Color Field painting is now a genre of its own. Unveiling these works was ludicrous, even dangerous, and his peers advised against it. Some of his most famous works from this series are Black in Deep Red, Light Red Over Black, Orange and Red on Red, and Four Darks in Red, known for their dark and intense nature, and they are some of the most emotional.

Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) in Suspiria, 1977

The color red takes up so much space in Suspiria, both physically and emotionally. The dance academy has five floors, two of which are student dormitories painted bright red. The whole building is maze-like, and we spend a great deal of screen time following Suzy and her friend Sara up and down long blood red hallways, around corners of crimson light, and into tiny flame-colored bathrooms and bedrooms. For much of the film, we are bathed in red on all sides unable to escape the color permeating our brains.

Sleeping in the Great Hall, Suspiria, 1977

In Light Red Over Black, Rothko makes a remarkable inquiry: sit in a place of feeling, whatever it may be, until you are done. Both Argento and Rothko insisted on redefining their craft by ways in which the public is required to engage with it. It is much easier to laugh at Suspiria’s mishaps than to engage with the unspoken elements of it, and it is much easier to become angry at an inexplicable abstract painting. As Rothko stated, “A painting lives in the eyes of the sensitive viewer.”

Throughout Suspiria, we see that our protagonist Suzy is also quite defiant. From the moment she steps into the dance academy, she is asking questions, challenging authority, and advocating for her own autonomy. At first, Suzy plans to board elsewhere, but when it becomes clear that she intends to defy the academy’s hierarchy, she is forced to stay at school. It’s unclear whether or not Suzy will eventually join the evil powers that be, or thwart them, but either way, she spends all of her screen time in direct opposition to whomever attempts to hold her down.

One evening, the ballerinas discover maggots falling from the ceiling onto their beds and into their personal belongings. Mayhem erupts, resulting in everyone moving to sleep in the great hall. But when the lights go out at bedtime, the scene is not dark. Instead we are bathed in intense red light that fills the entire screen. In this scene, Sara admits that she knows something about the girl who went missing the night that Suzy arrived. She tells Suzy about weird habits the teachers have, that they leave the school at night, and that she believes something is terribly wrong. Suzy’s defiance grows.

Four Darks on Red, Mark Rothko

There is a perpetual and cyclical bleeding out of color and emotion in the Rothko paintings, such that the viewer is easily overwhelmed. It is easy to see how one can pass them by without engaging, or to become so disgusted by their own reaction as to condemn the piece altogether. In Suspiria, it is unabashedly intentional. The cyclical nature of the story can be found everywhere: in the architecture, in the spiraling grand staircase and common room, in the pirouettes that first make Suzy sick, in the circular grand hall where they all must sleep during the maggot invasion, in the relays of color within a scene, in the repetitive patterns that the girls trace trying to figure out the mystery, and in the final room where Suzy finds a blue iris and discovers the truth.

Red, too, is a cyclical color—one that recalls menstruation, the life cycle, fire, blood, danger, and passion. It is an intense color, readily available in nature, and one that is hard to ignore. As Suzy’s friendship with Sara evolves, the girls try to solve the very obvious mystery of the missing dancer with theories of witches and the occult. Witch magic, blood magic, women’s magic—at a dance school run by women who are “malevolent by nature”—is all the explanation Suzy gets when she finally gets an answer. The red-hued set and evil witches are a heavy-handed metaphor on Argento’s part that leaves no room for imagination. Perhaps the strangest thing about Suspiria is that it is so straightforward. There are no surprises, barely any jump scares, and no plot twists. What you see is what you get. But that is exactly the point: Argento doesn’t really care about solving the mystery at all. He cares about drowning you in an overwhelming confusion and discovery.

Within these red labyrinthine walls, we are meant to feel lost. We follow Suzy and Sara down the rabbit hole, only to find what we already knew to be true. At some point Sara is lost forever, and Suzy rejects her fear to search for her friend. The climax of the film features Suzy defying authority by chasing after it, secretly, into the dizzying depths of the school to the very end, which eventually does end in a fiery red blaze. Suzy circles the red school until she scrapes the bottom of the well, much like the risky business of looking at a Rothko. One could perhaps drown in one’s own loss, or discover a way out.

Ultimately, Suzy’s defiance saves her. Her choice to walk into the dark in search of answers and to hold her ground in spite of a truly terrifying reveal is what breaks the cycle. She rejects the previous paths set before her, painting with color instead of form, and in doing so frees herself from becoming the very thing she rebelled against. Argento may not have been the most skilled director in many ways, but his ideas about what a film could be, rather than what it should be, make Suspiria worthy of investigation.

Suspiria, 1977

Light Red Over Black, Mark Rothko

Article written by Theresa Baughman

Theresa totally hates movies but sometimes watches them with her friends. She writes about the intersection of art & anthropology and she loves demonic possession horror.