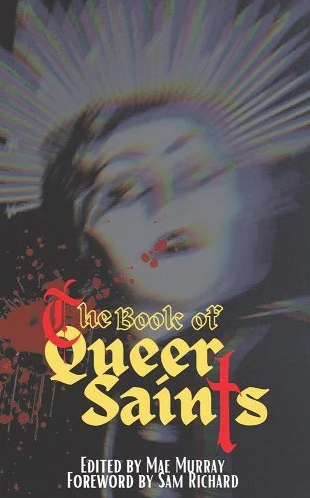

Book Review: “The Book of Queer Saints”

The Book of Queer Saints, an anthology of queer horror fiction edited by Mae Murray, is a groundbreaking achievement in horror fiction, and an exemplar of the current golden age of indie genre publishing. The Book of Queer Saints is both deeply messed and deeply joyous—this book is an act of solidarity for all those who struggle with their bodies, their identity, and their sexuality. But, most importantly, it showcases the importance of being able to live authentically, freely, and messy as hell.

If you look at the history of literature, you’ll likely see patterns of call and response between books, pertaining to themes, ideology, and social expectations. The Book of Queer Saints continues this tradition of books as a form of discourse, but in a way that reads as an incredibly sublime middle finger to those who only want harmless queer representation. In this instance, “harmless queer representation” refers to queer characters that are only ever portrayed as good, kind, or powerful—strictly positive qualities, generally speaking. Not allowing the literary space for queer characters to be fully and beautifully and messily human only serves the interests of the oppressor.

“ And, sometimes, this burning of the veil that hides us from the world can have monstrous results.”

This anthology showcases queer characters who are quite literally monsters, deeply emotionally flawed, abusive, codependent, messy, and at various stages of strange and beautiful relationships with their bodies. Every single one of these stories is completely unapologetic for the space many of these pieces of well-written body horror take up in the reader’s mind. And as a reader on the asexual spectrum, I related more to incredibly horny queer characters than I ever have to queer characters written with only positive attributes.

The challenge I often encounter with reviewing anthologies is differences in quality of stories, but in The Book of Queer Saints, that problem does not exist. The stories that I didn’t personally connect with at this time, I know speak to some future or past version of myself as a reader. If you’re queer, there’s some real part of you waiting to be found in these pages.

I am also incredibly honored to give Murray the credit she is beyond due: the list of authors in this anthology are many of the gems in the indie horror publishing scene: Hailey Piper, author of The Worm and His Kings; Eric LaRocca, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke; and Eric Raglin, editor of ProleSCARYet: Tales of Horror and Class Warfare. This is just to name a few: Every author here is absolutely just as deserving of reader attention.

As an anthology, The Book of Queer Saints stands out to me as powerfully thematic in ways I don’t often see executed successfully, especially pertaining to the body as a theme. There are stories of the body in transition, as can be read in Hailey Piper’s “We Frolic Within the Leviathan’s Heart,” when an amphibious being comes to land to collect wealth for her monstrous mother, but encounters a different kind of treasure. There are stories of the body as a fetishized object, as can be seen in “Crumbs,” by Joshua R. Pangborn, where the obese protagonist finds that he loves being in a feeder relationship, that is complicated when the person who feeds him is also abusive. There are also stories of the body as a source of deep joy and a fleeting moment of salvation, as can be read in the concluding tale, “Heliogabalus Fabulous” by Belle Tolls, a fictional account of a trans Roman emperor who sought to dance in a revolutionary new world of freedom, but she is destroyed. But, in the end, the joy comes from the dance she began. As Tolls writes, “Genderfuck; divinity!”

The Book of Queer Saints also showcases the playful side of being queer, how we are able to abscond with restrictive labels that only serve to oppress us. And, sometimes, this burning of the veil that hides us from the world can have monstrous results.

In Eric Raglin’s “Macramé Flames,” the protagonist returns to an old motorcycle gang that sought to summon the Devil by burning down a number of Hobby Lobbys. Along the way, the protagonist becomes reacquainted with an old love who realizes that white suburbia is the real Hell. And in “Therianthrope,” by Briar Ripley Page, the protagonist’s intensity becomes too much for the people around them—the protagonist becomes monstrous, Othered. These are only a handful of the stories in The Book of Queer Saints, and I think their power speaks for itself.

The Book of Queer Saints is for readers craving something violent, something real. By putting this book out into the world, joining the ranks of works like Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke by LaRocca, Mae Murray has shown queer folks that there is more than enough space for folks to be their real selves. Expectations of purity in representation only serve the oppressor. Now is the time of monsters.

Article by Laura Kemmerer

Laura tuned into horror with an interest in what these movies and books can tell us about ourselves and what societies fear. She is most interested in horror focused around the supernatural, folklore, the occult, Gothic themes, haunted media, landscape as a character, and hauntology (focusing on lost or broken futures).