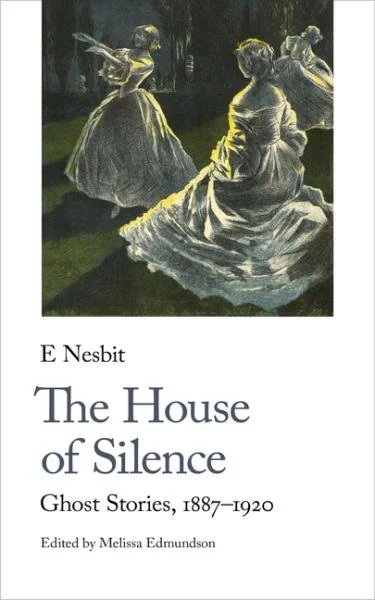

[Book Review] ‘The House of Silence; Ghost Stories, 1887–1920’

This review originally appeared in Dead Reckonings and has been reprinted with the permission of the author.

“They talk about death being cold. It’s life that’s the cold thing.”

If it were possible to sum up Edith Nesbit’s horror fiction in a single line then this quote from one of her final tales would be as good an attempt as any. As Melissa Edmundson tells us in her introduction “[Nesbit’s] characters are always hiding something … whether it be a disappointment, a regret, a fear, a screen, or a crime.” The gaps these acts of hiding create become, inevitably, filled with the chill of ghosts but Nesbit’s unexpected statement that life, not death, is cold also indicates some of the contradictions at the heart of her own life. Nesbit was an “imaginative and precocious child who enjoyed exploring the outdoors”—which comes through in some of her often beautiful descriptions of the natural world—who would grow up to become the author of beloved books for children like Five Children And It or The Railway Children. Yet she was also “miserable and confined at school” and “suffered great disappointments” in her adult life. Perhaps some of these disappointments came from Nesbit’s tumultuous personal life. Nesbit married Hubert Bland in the spring of 1880, when she was not quite 22, and the two of them were founding members of the Fabian Society; she in particular was an active and ardent supporter of social justice causes. But Nesbit did not know that Bland already had a child with Maggie Doran, and had kept the affair up into their marriage. Once the relationship was discovered Nesbit realized that Doran, for her own part, “knew nothing of Bland’s marriage to Nesbit or of Nesbit’s two children with Bland.” Yet it did not stop there. Bland went on to have a further affair with Alice Hoatson who moved into Nesbit’s household and acted as her housekeeper. Hoatson eventually gave birth to two children by Bland. Not even their progressive, permissive circle of social reformists could watch this without a raised eyebrow; no less a figure than George Bernard Shaw described how Bland “maintained simultaneously three wives, all of whom bore him children. Two of the wives lived in the same house. The legitimate one was E Nesbit.” Edmundson, blisteringly understated, notes that “accounts differ over the extent to which Nesbit approved of this situation.”

Even if she did approve, she must have had moments of feeling lost and betrayed, that life was “the cold thing,” and this comes through in her ghost stories. Edmundson quotes Nesbit’s biographer Elisabeth Galvin when she says that “[m]any of the stories centre around the deep sadness of unrequited love between a man and a woman, a sadness that manifests itself in psychologically disturbing ways.”

The House of Silence opens with “Man-size in Marble,” perhaps Nesbit’s most famous ghost story but certainly her most anthologized, and for good reason as it encapsulates most of her thematic concerns: the perils of love (or at least of passion); misfortune, guilt, and regret; how human relationships can crumble and collapse with the smallest misstep. Here we find a newly-wed couple, Laura and Jack, installed in their newly-bought cottage, surrounded by a “jolly, old-fashioned garden, with grass paths and no end of hollihocks, and sunflowers, and big lilies, and roses with thousands of small sweet flowers.” The genuine picture of domestic, if achingly middle-class, bliss is marred only by the sudden and ominous insistence of their housekeeper that she must take a leave of absence before All Saints’ Eve, a date tied with local superstition. The rest of the story is as inexorable as the implacable entities that carry it out but if the narrative suffers from inevitability then it also harbors a deep and haunting sense of unfairness; the tale’s victims seem to have done nothing to warrant their fates apart from, perhaps, having dared to be happy.

This unfairness also suffuses “From The Dead,” although in this case it’s the unfair actions of the protagonists against each other. Learning that he has been lied to in order to succumb to her affections, Arthur Marsh turns on his new wife Ida. He quickly repents—realizing that her lies were well-intended and, ultimately, led to happiness for them both—but not before she has fled, never to be seen again. At least, not until some time later when Arthur receives a curt telegram informing him of Ida’s imminent death. The grief and genuine regret for his hot-headed actions is drawn out until a single line, which I think is one of the most terrifying in all horror fiction, tightens it into an ice-cold point of terror. As Arthur sits in nocturnal vigil over his now-dead wife he hears “the same dear voice that I had loved so to hear” coming from the corpse; “‘I suppose,’ she said wearily, ‘you would be afraid, now I am dead, if I came round to you and kissed you?’” It is a moment of piercing clarity in a tale about miscommunication and misunderstanding, but one that is all the more horrible because of it.

Not all of Nesbit’s works are quite as bleak, however. “Number 17” shows the shared heritage of the ghost tale and the shaggy dog story as a guest at an unnamed hotel uses his rambling, salesman’s gift of the gab to bluff himself into a room upgrade. Whether “Number 17” is truly a ghost story is debatable but it’s a story about ghosts and, more importantly, a story about the dread of being haunted. This is the thread—that “life is cold” because it is the living who are haunted—that runs through the best of Nesbit’s work; the act of haunting, whether by more literal ghosts or the ghosts of one’s actions and inactions, sits crouching at the heart of “The Power of Darkness” or in the quick, shivering flip in tone that elevates “The Detective” to a masterwork. In the same way that James’s “Oh, Whistle And I’ll Come To You, My Lad” has such lasting power as Parkin remains haunted by his unexplained and inexplicable experiences even after the story has ended, Nesbit is at her best when these hauntings linger, unresolved. When the eponymous “House of Silence” ends with the line “There are no travellers on such a road at such an hour,” it repeats its opening line—as The Haunting Of Hill House, another work less about ghosts than it is about being haunted by a cold life, would some fifty-odd years later—to imply that the story isn’t just a single episode but a repeating limbo, perhaps related to the fate of the woman in a green gown we half-glimpse only momentarily.

Where Nesbit fails, at least for me, is when this subtlety evades her and she falls into a tweeness that erodes all sense of ghostly coldness. “The Haunted Inheritance” is a clumsy romance made doubly awkward by an overwrought narrative and the fact that the loving parties are cousins, something which may have been less of an issue in the early 1890s than it is today, but it falls flat precisely because its sprightly, rosy-cheeked resolution is happily resolved and life is warmed in love’s glow.

Yet, again and again, Nesbit succeeds in her aims of producing effective and affecting stories and, as Edmundsen states “the capacity of these narratives to haunt the reader’s imagination comes from their proximity to the everyday” before continuing to paraphrase M. R. James’s belief that “the most effective ghost stories are the ones that could happen to us.” Life, for many, often does feel cold. We are often haunted by ghosts not dissimilar to those that Nesbit teases out of that coldness.

The House of Silence is a bittersweet collection—filled, like life, with regret and disappointment but also sparks of humor and even joy—and it seems almost too ironic that its publication is even more bittersweet, as it brings to a close not only Handheld Press’s excellent run of forgotten weird fiction but also Handheld Press as an endeavor in its own right. It’s fitting, though, that this excellent collection of ghost stories, stories very much about absence and lingering, is what they’ve chosen to leave us with.

Article written by Dan Pietersen

Daniel Pietersen is the editor of I Am Stone: The Gothic Weird Tales of R. Murray Gilchrist, part of the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series. He is a recurring guest lecturer for “The Last Tuesday Society” and the “Romancing the Gothic” project, where he produces an ongoing series on Haunted Houses and related topics. He has also contributed criticism and reviews to publications like Dead Reckonings, Revenant and Horror Homeroom. Daniel lives in a very old house in a very old town and is slowly becoming very old himself. He occasionally appears on social media as @pietersender.

![[Book Review] ‘Crawling Horror: Creeping Tales of the Insect Weird’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1766154499255-F0L1IWN8LNDPWPCMZTTL/9780712353496.jpg)

![[Book Review] ‘Celtic Weird: Tales of Wicked Folklore and Dark Mythology’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1762547621282-28FMCLLSW6M2PZE2LY8W/celtic-weird.jpg)

Bones and roots adorn the walls of their dimly lit home. A mjölnir necklace hangs around K.’s neck as he hand carves incense into a small cauldron burner and a breathy soundtrack begins to play. This is a couple that is in tune—with themselves, with the natural world, and, as we will soon see, the supernatural world, as well.