Reading the Bible with Horror, Reviewed

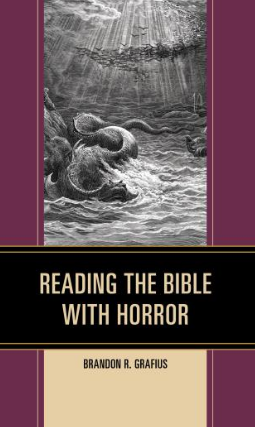

Art by Gustave Dore

The horror genre is a haunted house of many rooms, with the sweeping entrances of Blumhouse’s blockbusters to the creaking corners of A24’s arthouse. The library is aflutter with the ideas of writing greats like Victor LaValle, Stephen King, and Alma Katsu, alongside other authors showing just as much promise for their own careers. And in the midst of all this, there is the niche of genre analysis, some of which can draw the reader unexpectedly into hidden rooms.

One such book is Reading the Bible with Horror by Dr. Brandon Grafius. Grafius’ background includes a Ph.D. from the Chicago Theological Seminary in Bible, Culture, and Hermeneutics. In his most recent book, which was published in October, Grafius examines the Hebrew Bible’s Leviathan in context with monster theory and uses discussion of Derrida as a tool to take a look at the haunting landscape of the Bible, among other fascinating points. The vein of exploring the Bible and horror is a well-established phenomenon in Grafius’ work: Previously, he authored Reading Phinehas, Watching Slashers—a revised version of his dissertation. (Reading Phineas examines the story of Phineas through the perspective of horror.)

Reading the Bible with Horror is intended as a resource for researchers, but the writing also keeps the proverbial ladder down, inviting readers new to the intersection of critical theory and horror to the conversation. (As we continue to learn and grow as an online indie zine, these spaces to learn are incredibly helpful.)

In Reading the Bible with Horror, Grafius brings genre staples to intersect with elements from the Bible. The House of David is treated as a haunted house through expanding the definition of “house” to include the consideration of David’s children and their own actions. In another section, Derrida’s work is used as a tool to examine the ghosts that persist in the text, including the ghosts of the gods that the Israelites can never seem to completely leave behind.

The intersection of a religious text and the horror genre is one that I felt I should have realized sooner, but Grafius clarified wonderfully: Both the Bible and horror explore the depths of fear, anxiety, and other elements of our psychological dark side. Unlike in a romcom, horror never promises that things will turn out alright. God, an entity that we so often assume to be largely benevolent, has several moments in the Old Testament that are in line with a monster of chaos. There is also an element of the monstrous in creation itself.

The structure of the work is also fairly sound, situating the reader first in familiar territory with Grafius’ own personal account of his relationship with horror. Each following chapter remains grounded in the familiar for genre fans with the use of staples like ghost stories, haunted houses, monsters, and a number of other subjects. Additionally, chapters are helpfully grouped by theme. There are one or two conclusions, however, that interweave mentions of related horror films that read as somewhat anemic and short.

In my reading, one of the things that struck me most about Grafius’ book was how it also serves as a teaching tool for thinking critically within the genre. This begins with the idea that while at one point researchers would seek to find the explicit single, absolute “correct” reading of a text, methods have evolved over time, broadening interpretation to a point where readers may bring their own meaning. Though, again, this feels like something I should have realized sooner, encountering this kind of work and being included in the conversation around horror has encouraged me on a personal level to continue reading and writing critically within the genre.

Grafius’ writing talent is also noteworthy, deftly and easily bridging the gap between academic examination and readability for the layperson. The author takes steps to bring the reader up to speed, including an early outline of the general concepts behind contemporary monster theory. These additional details make it much easier to connect with the text and follow different lines of thinking. Diving into elements of Hebrew was also genuinely enjoyable and expanded my horizons as a reader.

For those interested in religious horror, or even the supernatural part of the genre, I would consider Reading the Bible with Horror essential reading. Religious horror often uses Christianity as an assumed “norm,” and hearing insights, stories, and philosophies from another faith casts an entirely different light on the subgenre. Grafius’ work also beautifully underscores horror’s power to let people express their lived experiences and fears in a way that bridges the gap to understanding.

Review by Laura Kemmerer

Laura tuned into horror with an interest in what these movies and books can tell us about ourselves and what societies fear. She is most interested in horror focused around the supernatural, folklore, the occult, Gothic themes, haunted media, landscape as a character, and hauntology (focusing on lost or broken futures).