FBI Agents, Serial Killers, and Red Lipstick: On Denise Bryson and Buffalo Bill

As a general rule, the early '90s weren’t a great time for trans representation as a whole, but especially not in horror media. After a decade of AIDS, cultural fears of queer people had been seeping into pop culture, specifically horror, for a while. Whole new genres even—slasher and splatterpunk—were created partly in response to AIDS. Emily Hughes says it best in her book Horror For Weenies: “During the AIDS crisis, the intermingling of blood and sex [in slasher and splatterpunk movies] had significantly different connotations for large swaths of the audience” (147). And trans people weren’t exempt from this fear and scrutiny. With movies like Dressed To Kill and Sleepaway Camp (which I admittedly have a soft spot for), trans people were jokes at best and monsters at worst, a trend that began with Norman Bates, then reiterated for different cultural climates and purposes. As Viet Dinh points out in his essay “Notes on Sleepaway Camp” from the collection It Came From The Closet, “Sleepaway Camp was simply the reductio ad absurdum of its siblings – Psycho, Dressed to Kill, The Silence of the Lambs – in which the murderer play-acts a different gender” (304). Psycho was released in 1960, Dressed to Kill in 1980, and Sleepaway Camp in 1984, all of which laid the groundwork for the eventual existence of The Silence of the Lambs. Given this timeline, the connection between the AIDS epidemic, the Satanic Panic, and crossdressing killers is undeniable throughout horror films, painting trans people as monstrous, murdering perverts.

Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) applies lipstick in The Silence of the Lambs. Image courtesy of IMDb.

In the '90s, after the precedent was set over the last decade, two wildly different trans characters were brought into existence just two months apart. The first, Special Agent Denise Bryson, DEA in Twin Peaks. The second, serial killer Buffalo Bill in The Silence of The Lambs. Denise Bryson’s arrival in the small town of Twin Peaks, Washington, aired on December 19th, 1990. On television screens around the world, and in what a 1990 issue of Entertainment Weekly called “the year’s best show” (Miller), Bryson walked into Sheriff Harry S. Truman’s office, where everyone was expecting a man named “Dennis,” and asked to be called Denise. She then proceeded to do her job calmly and competently, with utmost professionalism and respect from just about everyone around her, saving Dale Cooper’s life in the process. Two months later, on February 14th, 1991, movie theaters everywhere showed Dr. Hannibal Lecter claiming that Buffalo Bill only thought he was a transvestite because “Billy hates his own identity—and he thinks that makes him a transsexual” (Tally 55), which was part of why he’d killed his male lover, put him in a dress and makeup, and was making a woman suit” out of women’s skin. This characterization is, in many ways, reminiscent of Norman Bates, who could very well be the first example of the “cross-dressing killer” phenomenon (Dauber 342), which further solidifies this type of character choice as one of the past. So what the hell happened in those two months?

To start, the scripts for those characters were created further apart in time than when they were put on TV and theater screens. The Silence of The Lambs is an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s book of the same name, published in 1988. As such, the character of Buffalo Bill is better understood as an '80s character having been originally created in the '80s, despite being in a '90s movie. His portrayal is very in keeping with the standard “monstrous queer” tropes of the time. This continuing pattern of queer monstrosity is one that is clear in horror movies, which begins with Norman Bates in Psycho and continues with villains like Angela Baker, Leatherface, Freddy Krueger, Dr. Robert Elliott (Bobbi), and many more. The progression of this archetype can be tracked more closely in Janet Staiger’s essay “The Slasher, the Final Girl and the Anti-Denouement,” where Staiger compiles a series of tables which track characteristics—such as gender and motive, which are often interconnected—in slashers throughout the years. The killers are largely male, but their motives make it clear if it’s more complicated than that, including Norman Bates’s infamous motive in Psycho, as well as Buffalo Bill’s, which is listed as “cross-dresser needs skin” (Staiger). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Sleepaway Camp are both featured in these tables alongside The Silence of the Lambs. Denise Bryson, on the other hand, is a character that was created in the same year she arrived on television. Her placement in the middle of season two of Twin Peaks marks the beginning of a part of the show that received a lot of criticism and poor ratings, even by fans like Ben Durant and Bryon Kozaczka, creators of Twin Peaks: Unwrapped, because of its being comprised of several iffy and generally irrelevant plotlines that were caused by David Lynch and Mark Frost stepping away from the show for a while (Unwrapped 32 00:06:11). This meant that several different writers were tasked with somehow capturing the spirit of Twin Peaks without any real knowledge of where it was meant to be going. Harley Payton, who wrote the third episode, and produced many others, says of the last half of season two, “That was a big year for me and a busy year for me because I ended up doing a lot of the showrunning towards the second half of the second season” (Durant and Kozaczka 102). Caleb Deschanel, director of episodes 6, 15, and 19, is also quoted as saying that “I don’t think David [Lynch] had any idea how much work it was to do a show like that… [Mid-season two] felt a little bit more restrictive than it did in the earlier days of doing this show” (Durant and Kozaczka 103). All this to say, Denise was likely written just weeks before her episodes were filmed and released, with Payton’s statement communicating a sense of rushing and taking into account standard production time for television shows. Still, that’s only two years’ difference in their respective character developments. Denise’s first episode aired on December 19th, 1990, and her last episode of the original run aired on January 19th, 1991, which puts The Silence of The Lambs’s release a little less than a month after Denise left Twin Peaks, and Buffalo Bill as a character two years before that. So again, what happened?

David Duchovny as Denise Bryson in Twin Peaks.

Since establishing a timeline around these characters doesn’t provide as much clarity as was hoped, we must turn to the differences in the characters themselves. Namely, their pieces of media, costuming/hair and makeup choices, personalities, and acting choices. First, the media they’re in are, in many ways, shockingly similar. Twin Peaks is a horror show that centers on the murder of a young woman named Laura Palmer. It begins as a sort of offbeat investigative drama, then slowly draws the audience into a strange, Lynchian world of dreams, nightmares, and doppelgangers. The Silence of The Lambs begins as an FBI drama, and very quickly becomes a proper psychological horror movie. They have in common, not only the FBI agent protagonists, but also long-haired serial killers, distinctly psychologically terrifying plotlines and scenes, and serious amounts of gender blurring. Both also fit into the category of “prestige” or “artsy” horror, with Twin Peaks winning several awards during its run, including three Golden Globes and two Emmys, and The Silence of The Lambs making horror history in receiving five Oscars including Best Picture, as well as many other prestigious awards. Both Twin Peaks and The Silence of The Lambs also have significant elements of the mysterious and the surreal contrasted with the protocols and sensibilities of the FBI. However, in terms of trans representation, they are very different. In Twin Peaks, Denise is a hero, whereas Buffalo Bill is decidedly not. In many ways, especially in the characteristics portrayed by their actors, Buffalo Bill is a sort of anti-Denise Bryson.

To begin with, Denise is a very happy character. In every discussion about her transition, she is glad to talk about it, and glad it happened. She found herself in it, and has her own agency in every conversation she has about it. She chooses to introduce herself as she is, holds her own in that introduction, and is even happy to tell Cooper about how she realized who she was while they’re talking during the Milford wedding in episode 18 (“Masked Ball”). It’s quite a thing to tell your longtime friend and colleague that you discovered your true identity while cross-dressing for a drug bust, and she handles that conversation with grace and humor. She is a character defined by herself, and she is happy. Buffalo Bill, by contrast, is miserable. Hannibal Lecter says as much, having been Bill’s psychologist prior to his arrest. Buffalo Bill is defined by other people throughout the movie, never by himself. He is also rather incompetent. While his location and identity are set up as the big mystery of the movie, that case is solved by Clarice Starling and Dr. Hannibal Lecter—an FBI student and a homicidal psychopath, with the student doing most of the work. He’s not good at what he does, that being killing women and taking their skin. Denise, on the other hand, is wildly competent. She solves Cooper’s case in less than three days, gets him out of a hostage situation, and is incredibly professional through it all. She is there to do her job, and the fact that she now goes by Denise and uses female pronouns is introduced, and moved on from into the case almost immediately. What information she does give about her transition is at others’ requests, and again, handled with great professionalism. Her self-discovery is, in fact, tied to her job and competency—she was professional enough to dress as a woman while undercover, and realized that it felt right for her—and her discussion of this discovery with Cooper is both realistic and respectful. Her actor is also a contributing factor to this level of respect and positivity.

Denise Bryson is played by David Duchovny, who would later go on to play FBI Agent Fox Mulder in The X-Files (1993–2002). Duchovny approached this groundbreaking character with the same kind of respect that the show writers did. “I just remember approaching it just as, ‘Okay, if you’re a person and you found your true face or the mask that fits, how open would that make you?’” Duchovny said of the role, “and then I just went into every scene trying to feel joyful and open, finally comfortable, comfortable in my skin and my clothes” (Durant and Kozaczka 104). In short, this guy gets it, and his performance reflects that. He adapts distinctly feminine mannerisms while playing Denise, but isn’t over the top or camp with them at all. Ted Levine’s acting as Buffalo Bill, on the other hand, is a very over-the-top portrayal of the character. He is flamboyant and sleazy, everything about him overly exaggerated to the max. He plays Buffalo Bill accurately to the script, as the self-hating monster that he is written to be, determined by Hannibal Lecter, and society at large. And by those standards, it is a good performance. Buffalo Bill’s flaw is in his writing, as the character was written to be a cross-dressing freak of a serial killer, but Levine didn’t do anything to make the character any better, though there could have been room for him to do so. That said, in both cases, the costumes, hair, and makeup did a lot of acting for them.

Ted Levine as Buffalo Bill. Image courtesy of IMDb.

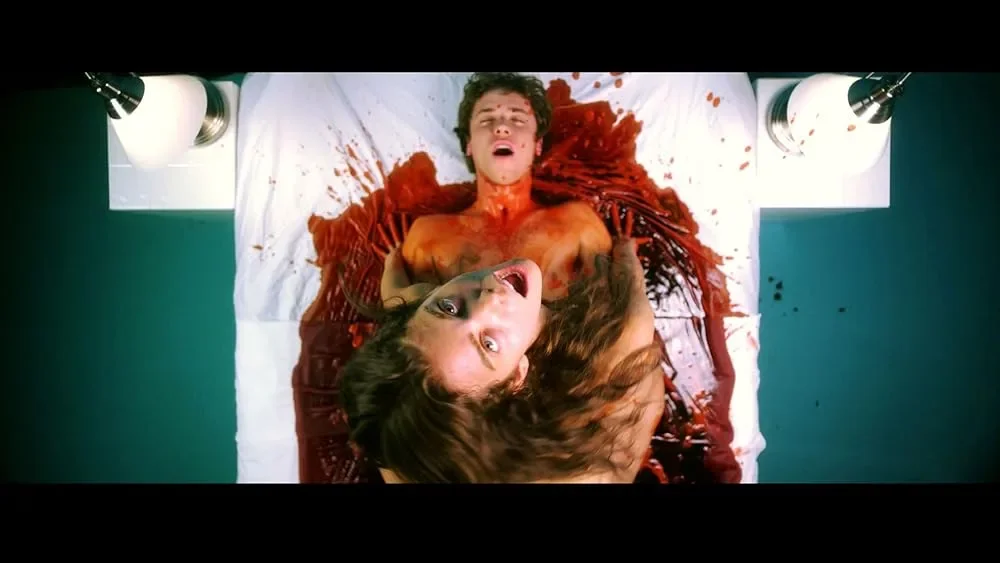

In most of David Lynch’s work, the characters seem like they were taken out of a 1950s melodrama into a strange, dark world of dreams, as Willow Catelyn Maclay describes on episode 60 of the acclaimed Twin Peaks podcast, Creamed Corn and The Universe, saying that “the women in Twin Peaks are typically characterized through past depictions of film-noir…which is really hip for the time period because the '80s just had this kind of obsession with the '50s, which David Lynch helped create” (Maclay). Twin Peaks is no exception, especially in its Emmy-winning costuming. The girls are dressed in plaid and sweaters, the guys are bikers, sheriffs, deputies, or agents, and the women are femme fatales. Denise Bryson follows this rule to a T. Her costumes are professional skirt suits, with jewelry and makeup to give a sense of style. When she saves Cooper, she wears a waitress outfit from the local diner with a gun hidden in her garter, accentuating the femme fatale aspects present in her behavior up until that point. She doesn’t take any nonsense, and her costumes show that. In fact, for the mission that ends in the hostage situation, she goes undercover as “Dennis” in a standard black FBI suit. However, it is clear through her mannerisms and speech during this scene, as well as those of the people around her, that this is not who she really is. Her gestures remain very fluid and stereotypically feminine, and she stands with her hands clasped in front of her in a way that could accurately be described as “demure,” as she bounces slightly on her heels. All other characters present, including Sheriff Truman, Deputy Hawk, and Agent Cooper, refer to her as “Denise,” and with feminine pronouns, and are visibly put off by her masculine appearance. In fact, the situation for which she dresses as “Dennis” is only put right when she shows up as herself. In a very stark contrast, Buffalo Bill is presented like a bastardized David Bowie. When dressing femininely, he wears a flowing robe that doesn’t cover his torso at all, a chunky belt, and makeup. When speaking to Clarice, he wears a vintage shirt and khaki pants combo that, for lack of a better way to say this, makes him look like a pedophile. So, Denise is portrayed and dressed as a beautiful femme fatale, while Buffalo Bill exemplifies almost every aspect of the typical queer monster in media: e.g. bastardized femininity, creepy pedophilic implications, reminiscent of lavender scare-style fearmongering about feminine men, etc. But they do have one thing in common: red lipstick.

Denise Bryson applies lipstick.

Both characters use red lipstick during important points in their plotlines. Buffalo Bill applies red lipstick as a finishing touch to his strange, Bowie-esque getup, a sign of completion, a kind of power applied to him that wasn’t there before. Agent Bryson reapplies her lipstick before persuading Ernie Niles, a drug dealer, to help her with Cooper’s case if he doesn’t want to end up in prison. In both instances, red lipstick on the character is a sign of power, of control. This is shown through very deliberate pauses to apply the lipstick—Denise before pressuring a drug dealer into working with her, Buffalo Bill as the final part of his grotesque, private transformation. Denise uses it to show Ernie the power that she has over him in this situation, while Buffalo Bill uses it in an odd private ritual of stolen femininity. With Bill, it’s menacing and off-putting in its use. Buffalo Bill gaining femininity through lipstick is not portrayed as a positive thing—but Denise using it to affirm her sense of self before threatening a man with prison, femme fatale style, very much is. Denise’s femininity being used in that way shows that she is, in fact, a woman and not just a man playing dress up, like Buffalo Bill.

Another way each of these characters’ identities is portrayed is through how other characters respond to them. Buffalo Bill’s existence is very isolated, giving the audience the sense that what he is is taboo—that and the fact that he kidnaps women and hides them in his house—so the only person we really see interact with him is Clarice Starling. She is hesitant in her conversation with him, hovering in his doorway at first, then frightened by what she notices about his behavior once inside his home. Everyone in the movie reacts to Buffalo Bill with fear and apprehension. While this likely has more to do with the fact that he is a killer than his cross-dressing, it still serves to further the idea of his monstrousness, his wrongness. In Twin Peaks, meanwhile, reactions to Denise are positive. Sheriff Truman shakes her hand upon being introduced to her, and while Deputy Hawk refuses at first, he shows her more respect as the episodes progress, referring to her correctly during the sting operation and making sure she’s safe. Dale Cooper expresses shock at first, then says “OK” when told her name. This is especially noteworthy because it is established in My Life, My Tapes: The Autobiography of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper that Denise and Cooper worked closely together before she transitioned, making his immediate acceptance of her all the more important (Frost 205-210). Cooper’s acceptance of Denise shows that trans people should be treated with respect, and referred to in the ways they prefer; that they are, even now, still the same person you knew, still the friend you had. This, to me, is the most important positive aspect of Denise’s character. She is not just happy for herself—the people close to her are happy for her, too. Which is how it should be in real life, and rarely is on television.

All of this just brings back the original question, however. How did these characters—one a wonderful example of representation, the other one of the worst—come into existence and the public eye so close together? The answer can be found, I think, in their respective pieces of media, and the people who made them. The Silence of the Lambs was made to shock people, to scare them, to make them sit up and think. It was meant to be grotesque, not quite beautiful, and unnerving, and playing into mid-AIDS fears of feminine and queer men was just about the perfect way to do that. It digs into the underbelly of America, much like David Lynch did, only in a grimier, less dreamlike fashion. While it is an undeniably brilliant movie, Buffalo Bill is a glaring flaw in it, and paved the way for further grotesque queer characters to be made, with characters like Longlegs still showing its reach today. Twin Peaks is meant to take the audience into a dream; a dark, nightmarish mirror of Americana. Twin Peaks was created out of love and spirituality, and even the episodes David Lynch didn’t have a hand in show that. In a show about love, exploration, and beauty, to have a woman like Denise Bryson who was happy, respected, and professional isn’t so entirely out of the ordinary. Her character is treated with love and respect because all characters in Twin Peaks are treated with love and respect. These characters coming out so close together is not indicative of a massive cultural shift in views of trans and gender nonconforming people over that two-year/two-month span. In fact, things got a whole lot worse for trans people in the '90s and 2000s than they already were (Maclay 00:33:33); the climate surrounding trans people only started getting a little better with the advent of social media. The difference between these characters is more indicative of the fact that different people had different reactions to AIDS, and attitudes towards queer people as a result. Denise Bryson and Buffalo Bill are not either of them exemplary of the views the general public had towards trans people, nor the views the groups of people that watched them had towards trans people. They are instead exemplary of their creators’ views on trans people, which just so happened to fall on opposite ends of a spectrum.

So, in terms of early '90s trans representation, there first came a woman who introduced herself as she was, did her job, did it well, fit the aesthetic of the other women in the show, and was happy with who and how she was the whole time. Then came a man who thought he was a transvestite out of self-hatred and killed women for it, taking their lives and skin to make himself who he had decided he was. It is important, I think, that both these characters exist in contrast to each other. A trans character who is reasonable and beautiful, and a trans-coded character who is psychopathic and grotesque. They are opposite ends of a spectrum of representation, and can be used in comparison with each other to show what good representation is and what it means. In short, good representation is like Denise Bryson: happy, beautiful, and most of all, clearly equal to the other women in that piece of media. And she’s not only human in a way that Buffalo Bill is not, either. In every aspect of her character that I’ve covered: acting, writing, reactions, costumes, etc., she is recognized as a woman. A real woman, respected as she truly is. And that’s what is most important in trans representation, especially in a genre that is prone to monsters, and especially now. That all trans, queer, and trans-coded people be written, directed, costumed, and acted as they are: humans worthy of respect.

-

Dauber, Jeremy. American Scary. Algonquin Books, 1 Oct. 2024.

Dinh, Viet. “Notes on Sleepaway Camp.” It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror, edited by Joe Vallese, Feminist Press, 2022.

Durant, Ben, and Bryon Kozaczka. Twin Peaks Unwrapped. 8 Apr. 2020.

———. “Twin Peaks Unwrapped 32: S2E18.” Twin Peaks Unwrapped, 13 Jan. 2016, open.spotify.com/episode/4L9nhymhU6jVhQdGWkOqjP?si=5YwSemL2SV28DWQj1b5_pQ.

———.“Twin Peaks Unwrapped: 36 S2E20.” Twin Peaks Unwrapped, 10 Feb. 2016, open.spotify.com/episode/6CEVJQYORuYXXzKdmTQCPr?si=u9u9Bg96TkC_v3rspDUqGQ.

Frost, Scott. The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper. Penguin Books, 1991.

Hughes, Emily C. Horror for Weenies. Quirk Books, 3 Sept. 2024.

Maclay, Willow Catelyn. “Denise Bryson.” Creamed Corn and the Universe, 26 May 2024, open.spotify.com/episode/74NFx1DTHeYOVuI0timUTM?si=R0Zqbe_HRryYMT5pkELfjw.

“Masked Ball.” Twin Peaks, created by Mark Frost and David Lynch, written by Barry Pullman, performance by David Duchovny, season 2, episode 18, ABC Entertainment, 1990.

Miller, Steven. “Twin Peaks in Entertainment Weekly from April 6, 1990.” Twin Peaks Blog.

Steiger, Janet. “The Slasher, the Final Girl and the Anti-Denouement.” Style and Form in the Hollywood Slasher Film, edited by Wickham Clayton, Basingstoke, Hampshire, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 215–217.

Tally, Ted, screenwriter. The Silence of the Lambs. Directed by Jonathan Demme, Orion Pictures, 14 Feb. 1991.

Article by Blaise Balas

Blaise Balas is an avid horror watcher, reader, and writer. She is the creator of the blog So Desensitized, which seeks to dispel the myth that "kids these days" don't understand or appreciate horror media. Blaise absolutely adores Twin Peaks, and is fascinated by everything wonderful and strange. Find Blaise on Instagram @blaisebalas.

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”