Mexplatterpunk: How to Write with Blood

Introduction

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term mexplatterpunk. When I refer to mexplatterpunk, I don’t intend to define a literary movement or categorize the wide horror spectrum produced in Mexico as “Mexican splatterpunk.” What I aim to do is use the concept of what the splatterpunk subgenre represents as a metaphor to understand a particular expression of Mexican horror, one that emerges from the subversion of some horror subgenres in contact with social reality and its cultural condition. My argument is that a portion of the horror produced in Mexico manifests as mexplatterpunk: a hybrid entity, a homunculus born from the organic subversion and fusion of elements from splatterpunk, Mexican and Southern Gothic, and Asian horror, reflecting systemic violence—the decay of Mexican reality. To explore this thesis, it is necessary to outline the definitions of the aforementioned subgenres and then highlight the respective elements that constitute mexplatterpunk. Once this has been done, we may proceed to examine its interaction with Mexican cultural reality and the production of horror, culminating in the metaphor of hybrid horror represented by the homunculus.

Definitions (Sighting)

Splatterpunk is a subgenre of horror that emerged in the 1980s as a rebellion against traditional, mildly suggestive horror (Sammon vii), and as a critique of social and political issues (Tucker 11). Its main characteristic is its exploration of taboos, employing graphic depictions of torture and violence while explicitly conveying sociopolitical critiques in the narrative structure. A key work of this subgenre is Clive Barker’s Books of Blood. At this point, it is important to distinguish it from extreme horror. While both use the body as an object of violence, extreme horror does not carry the explicit political or social critique of splatterpunk. That is, extreme horror arises after splatterpunk, focusing on pushing the limits of gore solely for impact (Duda).

Southern Gothic is another American subgenre that flourished in the twentieth century, after the Civil War (Malin). Its main characteristics are the use of the grotesque and macabre elements in socially outcast characters, framed within oppressive and decadent settings, without losing the supernatural traits typical of Gothic literature.

To discuss Asian horror, I generalize the horror produced by different Asian countries due to its shared defining characteristic: the influence of their respective folklore and mythology on horror production. This results in original ways (Kengskool 35) of approaching fear compared to the Western style (Choi and Wada-Marciano). The irresolution (Boey) is the component I highlight from this subgenre which, incidentally, also has ancestral roots in both immortal and vengeful spirits of folklore (Anesaki) and in the sense of powerlessness before oppressive social structures. The idea that evil can be identified but never entirely defeated, and that, as a result, it transcends generations and can affect more than one individual at a time, is what makes open or unsolved endings the subgenre’s mechanism for reflecting on the inevitability of evil.

Having defined the subgenres, the next step is to explore how the elements drawn from each subgenre organically merge with Mexican reality. The following section analyzes how horror production in Mexico employs elements from the aforementioned subgenres, not to imitate or localize them, but to create its own distinct expression.

Horror in Mexico (Thickening)

Splatterpunk as reflection

It is unlikely that the visceral violence reflected in Mexican horror production is a deliberate stylistic choice. In most cases, these representations function merely as the narrative context, mirroring the harshness of the country’s lived reality. Thus, Mexican horror rarely seeks new forms of brutality, since social reality itself is already violent. Reservoir Bitches is a collection of short stories that vividly portrays the perspective of Mexican women who fight and survive in a harsh reality. One of the most recent examples of this reality is the massacre of the LeBarón family. Nine of its members (three women and six children, aged between eight months and twelve years) were shot and burned inside the vehicle they were traveling in, allegedly after being mistaken for a rival cartel (Ventas).

Mexican Gothic

Although Mexican Gothic has its own historical roots, it coexists with echoes of the Southern Gothic from another era. In this context, decay refuses to disappear; it is a prolonged present, a consequence of the historical marginalization of rural centers and vulnerable groups. Also, grotesque characters vividly embody violence, while institutions and systemic corruption resonate as modern incarnations of oppressive, supernatural forces. Authors such as Bernardo Esquinca and J.J. Mason are known for blending the supernatural with crime fiction, exploring either the urban Gothic of Mexico City or old haciendas that recall the roots of the Gothic in Mexico.

One of those rural echoes comes from certain indigenous regions of Chiapas, where entire communities have been forcibly displaced, whether due to natural disasters, religious conflicts with other communities, or more recently, resistance to extortion by cartels. This last reason led to an attack one early morning in the village of Tila, Chiapas (McDonell), where cartels opened fire on every house. Of the thirty families that made up the village, only a few managed to flee for more than two hours, seeking refuge in Guatemala. It is presumed that those who disappeared were forced to work for the cartels. The film Prayers for the Stolen echoes this reality, portraying a community besieged by forced labor for cartels and human trafficking of women and girls, whose fear and resilience give the story its emotional weight.

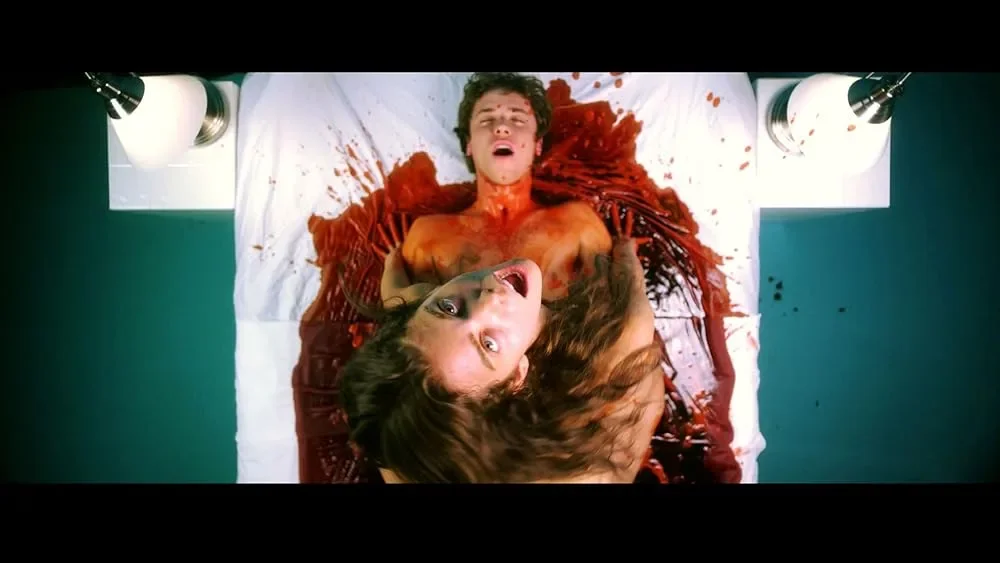

Issa López’s Tigers Are Not Afraid (2017)

Irresolution as a source of horror

Irresolution in Mexican horror is not a deliberate narrative device. Like the elements discussed earlier, it reflects the impunity in real life. The fatalism in Mexican horror productions stems from this lack of justice, whose harms are perpetuated and transcend generations. Although these enduring evils do not have a cosmic or supernatural origin, as in Asian horror, they operate indefinitely without resolution, affect more than one person at a time, and reflect the fatalism of collective frustration. Films that explore all these themes are: Tigers are not Afraid, Sujo, and Identifying Features. While a real-life echo of these stories can be found in the work of Pulitzer Prize winner and recent Nobel Prize nominee Cristina Rivera Garza, who in her book Liliana's Invincible Summer: A Sister's Search for Justice tells her thirty-year struggle with the Mexican justice system’s failure to find her sister’s killer, murdered in the 1990s.

With all these elements present, it’s clear that Mexican horror is not merely an adaptation of imported subgenres, but an organic manifestation of both reality and theory. At this point, it is worth noting that one distinctive characteristic of this manifestation is the way the theoretical line blurs between the definitions of terror and horror. Yet the line fades only to intertwine, becoming part of the same experience. For this reason, I have consistently used the word horror throughout this essay, without distinguishing it from terror. The following section explores how the organic fusion of these elements gives rise to the concept of mexplatterpunk, as a metaphor for this uniquely Mexican horror.

The mexplatterpunk: the manifestation of the homunculus (Revel)

Mexplatterpunk is a homunculus that arises from the subversion and fusion of certain subgenres’ elements in contact with Mexican reality. This approach is explained in detail below.

The main characteristic of splatterpunk, as previously seen, is the use of gore as a technique to create impact, using shock to confront taboos and deliver sociopolitical critiques. However, in the Mexican context, explicit violence has become normalized within everyday reality (as exemplified in the previous section). As a result, the intent to provoke reflection through shock loses some of its power in this setting.

Therefore, when a Mexican horror production aligned with the concept of mexplatterpunk utilizes gore, it doesn’t replicate the original intention of splatterpunk. Instead, the gore is theoretically reconfigured. That is, the purpose is subverted from A to B:

| Gore | ||

|---|---|---|

| Splatterpunk (A) | Subversion | Mexplatterpunk (B) |

| *Gore to shock → leads to reflect → transgressive | to shock → to document & transgress → fatalism | *Gore to document → *leads to reflect → resignation |

*So while mexplatterpunk does not invalidate its critical function, its reach is limited. This is because it appeals, first, to the people who live or are familiar with the reality it documents, and second, to those who are not overly desensitized to violence.

Southern Gothic keeps its defining characteristics (social decay, oppressive institutions) almost unchanged. Its adaptation involves a slight, modern reinterpretation and combinations with Mexican Gothic. Unlike splatterpunk, which changes the original motivation, here the essence is preserved in every element, simply by updating the context or origin.

| Social Decay | ||

|---|---|---|

| Southern Gothic (A) | Subversion | Mexplatterpunk (B) |

| *Communities trapped → in devastation of history → unable to adapt | history → actual | Communities trapped → in unpunished violence → unable to adapt |

| Oppressive Institutions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Southern Gothic (A) | Subversion | Mexplatterpunk (B) |

| Ghosts → as collective traumas → from violence and slavery | Ghosts as symbols of the past → Narco as a reflection of the present & other main institutions, such as the patriarchal family, religion, and legal system are already present in Mexican Gothic | Narco → as collective traumas → from violence and slavery |

| Grotesque Characters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Southern Gothic (A) | Subversion | Mexplatterpunk (B) |

| Deformities or unusual appearances that make them outsiders → twisted by obsession or cruelty → evoke both fear and pity | Grotesquerie reflects social hypocrisy or social inequalities → grotesque characters reflect narco culture and its inherent violence | Occasionally they are discernible, while other times they are indistinguishable from society → twisted by obsession and cruelty → evoke fear and pity |

These reinterpretations maintain its subversive quality. Thus, just like splatterpunk, Southern Gothic is subverted to become a tool for documentation, contributing to the creation of mexplatterpunk.

For Asian horror, irresolution is an intentional ambiguity. Its adaptation to reality is just as organic as the other elements.

| Irresolution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Asian Horror (A) | Subversion | Mexplatterpunk (B) |

| Supernatural can't be isolated from human being → No justice or end → Cycle of evil continues | Folk and Myth as the origin of irresolution → Corruption and impunity as origin of irresolution | Violence can't be isolated from life in Mexico → No justice or punishment → Cycle of evil continues |

One aspect of horror in Mexico has a unique relationship with its society (Mexplatterpunk), as it not only depicts it but also coexists with it, including its folklore (Sartini). Moreover, when elements drawn from splatterpunk, Southern Gothic and Asian horror are subverted, it reinforces the theoretical legitimacy of Mexplatterpunk as a distinct form of horror.

Conclusions (Aftermath)

As a hybrid horror entity, mexplatterpunk is a germination that could only arise in a Mexican context, where systemic violence reaches even into folklore. Mexplatterpunk is also a reflection of this reality. Its visceral violence, social decay, and persistent irresolution create a mirror that forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth.

Even though horror in Mexico is perceived instinctively, the value of this analysis does not lie in revealing some secret, but in giving a name to a cultural phenomenon. The idea of mexplatterpunk is not intended to encapsulate all the richness and variety of Mexican horror, but rather to offer a tool for understanding one of its rawest and most visceral manifestations, the one that emerges as an organic reflection of social reality.

Ultimately, mexplatterpunk forces us to rethink the role of horror as a critical tool in a society where violence has been normalized. If horror is weakened in a context like this, what should be the path forward? Should we devise new techniques for reflection? Should we continue until it becomes sterile? Perhaps we have reached a degree of dehumanization that is reflected in the loss of our ability to be shocked. Perhaps the real nightmare is not mexplatterpunk itself, but what it represents.

Mexplatterpunk doesn’t just entertain; it opens an opportunity for new voices to emerge from every corner and document their fears and anxieties, where the voice of the homunculus is heard louder than any other. This being moves at ease through the urban and rural Gothic. It coexists with ancestral folklore and imagines new legends. It is present in crimes, and impunity is the elixir that makes it both omnipresent and omnipotent. When the homunculus makes its presence known and speaks, most of us resign ourselves to listening in silence.

-

Anesaki, Masaharu. “Japanese (Mythology).” The Mythology of All Races, edited by Louis Herbert Gray, vol. 8, Archaeological Institute of America, Marshall Jones Company, 1928.

Boey, Danny. “The National Specificity of Horror Sources in Asian Horror Cinema.” 2012. Queensland University of Technology, dissertation. ePrints QUT.

Cerda, Dahlia de la, et al. Reservoir Bitches: Stories. First Feminist Press edition. Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2024.

Choi, Jinhee, and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano, editors. Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong UP, 2009.

Duda, Michael R. Extreme Horror Fiction and the Neoliberalism of the 1980s: Splatterpunk, Radical Art, and the Killing of the Collective Society. 2020. Purdue University, doctoral thesis.

Kengskool, Kittisak. “Thailand's Financial Crisis and the Media's Role.” The Journal of International Communication, vol. 5, no. 2, 1998, pp. 32-47.

Malin, Irving. New American Gothic. Southern Illinois University Press, 1962.

J. McDonell, Patrick. “Drug Cartel’s Turf War in Mexico’s Chiapas State Sends Villagers Fleeing to Guatemala.” Los Angeles Times, 22 Aug. 2024, p. 11, www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2024-08-22/drug-cartels-are-fighting-for-turf-in-the-mexican-state-of-chiapas-villagers-are-fleeing-to-guatemala.

Prayers for the Stolen. Directed by Tatiana Huezo, Pimienta Films, 2021.

Rivera Garza, Cristina. Liliana's Invincible Summer: A Sister's Search for Justice. Hogarth, 2023.

Sammon, Paul M. Introduction. “We're Not in Kansas Anymore." Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, St. Martin's Press, 1990, p. vii.

Sartini, I. “The Re-signification of the Myth of Llorona Through the Ages: From Myth to Political Performance.” European Public & Social Innovation Review, 10, pp. 1-14, 2025, doi.org/10.31637/epsir-2025-832.

Sujo. Directed by Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez, Corpulenta Producciones / EnAguas Cine / Pimienta Films, 2024.

Tigers Are Not Afraid. Directed by Issa López, Filmadora Nacional / Peligrosa, 2017.

Tucker, Ken. "The Splatterpunk Trend, and Welcome to It." The New York Times, 24 Mar. 1991, p. 11, www.nytimes.com/1991/03/24/books/the-splatterpunk-trend-and-welcome-to-it.html.

Ventas, Leire. “Qué fue de la familia LeBaron, la comunidad mormona de México que fue blanco de una brutal masacre que 5 años después sigue rodeada de incógnitas." BBC, 27 Nov. 2024, www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/c98ez673dj9o.

Article by Christian Dávalos

Christian Dávalos is a writer based in Mexico. He studied Creative Writing at the postgraduate level at the University of Salamaca, Spain, and is a member of the Horror Writers Association. You can follow him on Instagram at @chrisdavaloshorror.

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”