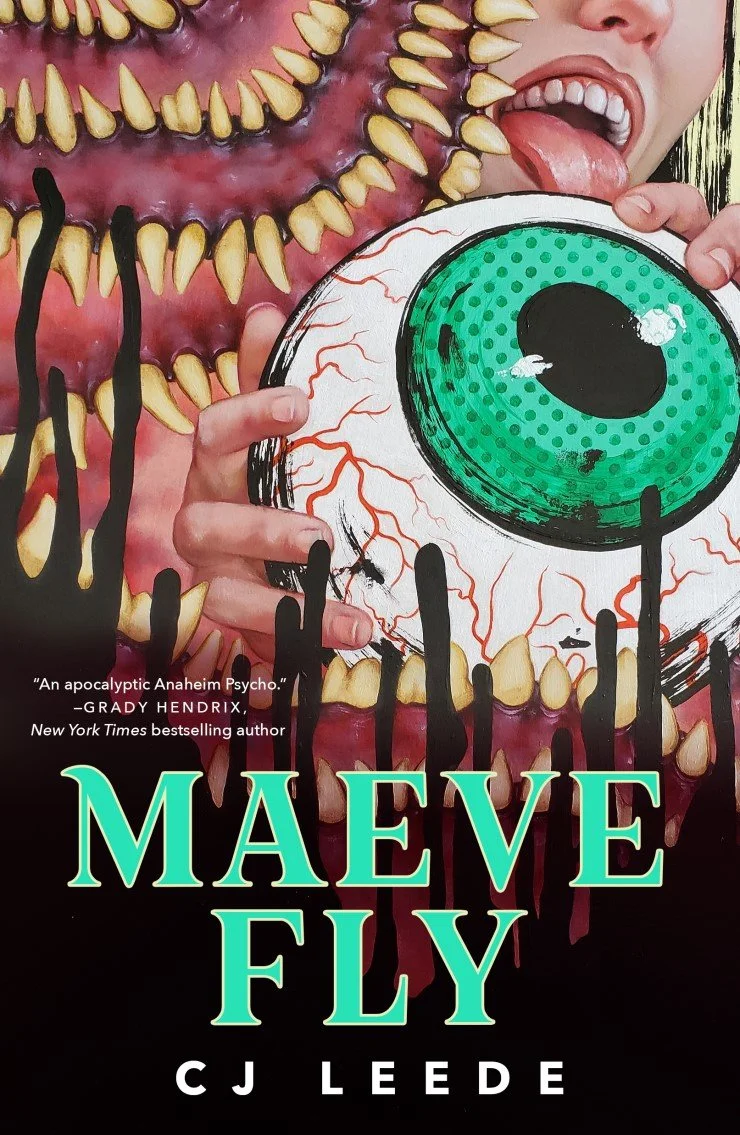

[Book Review] ‘Maeve Fly’ by CJ Leede

Maeve Fly is a princess. That is, she is an actress who portrays a popular ice princess at a large, unnamed and—I’m sure—entirely fictional theme park south of Los Angeles. She is also cynical, vulgar, unsympathetic, and struggling to control her violent urges. That’s pretty much all we know at the start of CJ Leede’s debut novel, Maeve Fly.

Even before its release on June 6, Maeve Fly has been building its reputation as a brutal, twisted addition to slasherdom, and we can go ahead and rip that band-aid off right off the bat—it’s a deserving reputation. Leede takes her time in building up to the mayhem, but it’s time well-spent, showing readers what makes Maeve’s brain tick in great detail.

Maeve is refreshingly complex, as far as antiheroes go. She is positively misanthropic, but she loves her job to death, despite it involving day upon day of countless interactions with children and families—a mandatory smile glued to her face. She’s good at it, too. In fact, even her rival and “unofficial” supervisor Liz, has to concede that Maeve, along with her best friend Kate (as the ice princess’s royal sister), garners more positive feedback from visitors than any other princess in the park.

Likewise, the love she feels for the city of Los Angeles runs as, if not more, deeply. The glowing descriptions Maeve uses as she moves around town make clear that she believes she understands L.A. more completely than anyone else—as if she alone holds the key to the soul of Hollywood. She is whip-smart. She reads Dostoevsky in its original Russian and philosophers Georges Bataille and the Marquis de Sade (both notorious for their pornographic fiction and hedonistic ideas), in their original French. She rattles off facts about the city and her favorite horror-punk bands and Halloween songs, and is exceptionally quick-witted. Prior to Maeve’s unraveling, you might be forgiven for reading the book as the writings of a morose, misunderstood introvert desperately clinging to her accepted vision of normalcy. Once her more “eccentric” proclivities begin to come into focus, however, you begin to see how any deviation from her vision might take us from dealing with Holden Caulfield to Patrick Bateman.

Leede clearly has a gift for drawing readers in and keeping them in as she builds her characters. We’re never given too much—constantly on edge as Maeve’s carefully constructed plans begin to fall apart. We get to see every step down into darkness Maeve takes as she releases herself from her bonds, taking full control of “the wolf,” as she calls it. Meanwhile, secondary characters—who are only ever seen from Maeve’s point of view—are given plenty of room to exist in their own right, often pursuing motivations that Maeve either misinterprets or misses completely.

Given the centrality of Bataille and Sade to the story and the sheer debauchery that Maeve finds herself in, I’m looking forward to a second reading so I can explore whether (or to what extent) Leede subscribes to Susan Sontag’s tying of pornographic content, not to sex, but to death. Granted, her connection of the two is explicit enough, in Maeve’s actions, if not in her words; but, if consistent, would add a vital lens through which to empathize with her main character. In fact, it’s Sontag’s essay, “The Pornographic Imagination,” that credits Bataille with connecting “extreme erotic experience” with death by “invest[ing] each action with a weight, a disturbing gravity, that feels authentically ‘mortal,’” a method which Leede uses to great effect in Maeve Fly. Far before things start to get nasty, Leede’s protagonist has a way of dealing devastating blows, even when the climax of the scene isn’t death.

Prefer listening to your books? Support WSB and your local bookstore by getting your copy from LibroFM!

There are only a few parts where the book nearly loses me. Early in the story, while we’re still being introduced to Maeve’s character and how she thinks and sees the world, there are a couple of instances where words or phrases will pop out of place, whether they are meant to highlight Maeve’s disconnection from others or her sociopathic tendencies, it’s as if these were deadline revisions that didn’t get the chance to fully marinate with the text. It’s a rare occurrence, and only worth mentioning to not let it dissuade you from continuing. The more jarring part comes later in the novel after we’ve come to know her thought process fairly well, Maeve begins to adopt a more Bateman-esque tone that, in her mouth, sounds a little too contrived for what we’ve come to expect from her. Admittedly, this comes well after she explicitly finds her inspiration in her copy of Ellis’s American Psycho, but it’s a shift that I wasn’t prepared for.

Still, Maeve Fly is an impressive debut that doesn’t hold back. Leede is fearless in her willingness to explore some of the darkest corners I’ve seen in a long while, giving us a character who is a thrill to follow, and who keeps us guessing until the traumatic final pages. Maeve Fly is frightening, it’s gross, it’s disturbing and tragic. But most of all, it’s fun as hell to read.

Thanks to Tor Nightfire for an eARC of Maeve Fly in exchange for an unbiased review.

You can support WSB by purchasing your copy using our affiliate link below!

Article written by Ande Thomas

Ande loves the intersection of sci-fi and horror, where our understanding of the natural world clashes with our fear of the new and unknown. He writes about monsters and foreign horror and can also be found over on Letterboxd.

Throughout the decades, slasher film villains have had their fair share of bizarre motivations for committing violence. In Jamie Langlands’s The R.I.P Man, killer Alden Pick gathers the teeth of his victims to put in his own toothless mouth in deference to an obscure medieval Italian clan of misfits.