Diving into Dahmer: A Serial Review

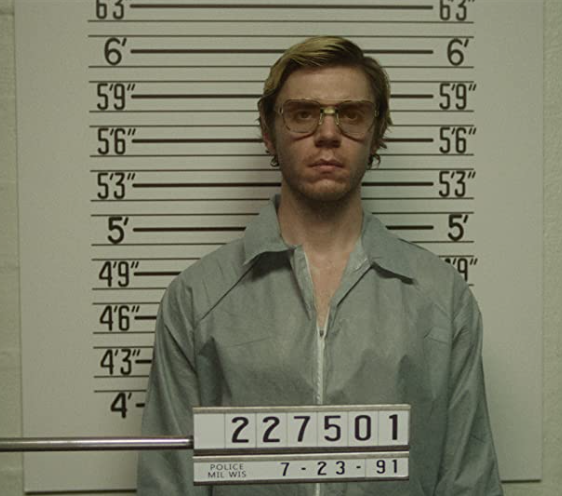

Image via IMDB

Dir. Ryan Murphy

Actor Evan Peters

At the beginning of October, Netflix released Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. The series is yet another adaptation of what infamous serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer’s life and murderous encounters might have been like. While any honest, raw true crime would respect the story and tell it about those who no longer can, I’m not so sure the balance of good and evil was all that we’d hoped it would be in this representation.

Similar to some of the stories portrayed in Murphy’s popular anthology series, American Horror Story, the 10-episode feature centers around true events, while several details and instances had been allegedly edited for theatrical effect and entertainment. In this review, I’ll not only cover those aspects of the series but also the importance of the rendition, as well as its unnecessary, retraumatizing effects.

Opening scenes from Episode One guide viewers through the capture of the Milwaukee Cannibal (or Milwaukee Monster) by police. From here onward, watchers are simultaneously taken through chaptered recountings of the killer’s past at varying milestones and behavioral changes, to what becomes his present arrest, trial, and death.

“It's hard for me to believe that a human being could have done what I've done, but I know that I did it.” - Jeffery Dahmer

True Crime Fascination

As a white female, I'm aware there have been a lot of discussions surrounding why exactly my specific demographic is drawn to true crime. While many are repulsed by it, there are some of us that are undoubtedly drawn to the genre. Not entirely our fault, Western society has developed a morbid fascination with true crime since the coverage of the Jack the Ripper murders in crime newspapers across Britain in the 19th century.

Fast forward to the 1970s when Americans were surrounded by stories of serial killers (when the term was in its infancy) such as Ted Bundy, Edmund Kemper, and John Wayne Gacy, among others. By the early 2000s, there was enough evidence connecting white women’s interests to true crime that Amanda Vicary, an associate professor of psychology at Illinois Wesleyan University, co-conducted a study titled, Captured by True Crime: Why Are Women Drawn to Tales of Rape, Murder, and Serial Killers?

“I think the true crime community likely follows along with the focus of the media, and we know the media likes to cover stories of young white women that go missing or are murdered,” Vicary said. “These are the cases that get the attention and then get covered by true crime podcasts and shows.”

While her study is over a decade old and primarily referred to true crime texts, we can compare the findings to the Gabby Petito case, which took the media and many social platforms by storm. Just as warning signs of her relationship with Brian Laundrie or the criticism of how police properly or improperly carried out their duties were plastered alongside the aftermath of her death.

However, regardless that Vicary went on to note that she has witnessed an uptick in coverage of cases involving missing or murdered Black or other marginalized victims, we could further observe (and will be later in this article) the issue of the lack of equal coverage and how it also affects the true crime genre.

I think for me, it was growing up and my newfound love for nonfiction was where I found a greater desire to know why and how these murders happened. Not just to protect myself, but to learn from any mistakes and hope that someday these types of cases would dwindle.

I think, to Vicary’s point, that not only do we sometimes see these victims as people we can connect with because of our shared demographic, but because the media is telling us we need to better protect ourselves and look out for red flags. In a separate study, Toronto-based psychotherapist Liza Finlay found that more women were drawn to true crime to learn from the stories as a means to better protect themselves. “Women watch to feel empowered,” she said.

Another interesting take that aligns with this article is that of Adam Golub, a professor of American Studies at Cal State Fullerton, who observed the connections between true crime narratives and pop culture. Golub says that if we are to truly learn from these true-crime retellings, we have to recognize explicit references and what they say about society’s fears, anxieties and the collective ability to cope with violence.

“Pop culture is a place where choices are made—choices about the stories we tell and the stories we don’t tell, the people and events we remember, and those we forget,” said Golub. “Real criminals become part of our meme and remix culture, circulating with fictional characters and other types.”

The question I have, then, is as a white woman, why do I care about one serial killer’s story, as it has been visually retold four times in the last five years—14 times since 1992 in terms of TV shows, docuseries and movies? Why should anyone? And most importantly, what is its purpose in pop culture? And does that purpose serve the public? At what cost to the well-being of the victims’ families and friends?

Past and Present Events Call for Review

Over the past few years, our nation has shed light on (and attempted to reckon with) the injustices its Black and other marginalized peoples continue to suffer. Consider any of the cases that made national news, such as those surrounding George Floyd, Breonna Taylor or Ahmaud Arbery. While these references are certainly decades more recent than Dahmer’s crimes, it still brings attention to the lack of protection, or same-level care, paid to equal-standing members of our community.

Just as observed in Monster, as a result of his crimes and his victims (14 of 17 total being people of color) Dahmer was accused of racially and demonstrably profiling his victims. Whether they were of color, gay, or low-income, Dahmer would lure his victims, drug them and then kill them before they could get a chance to leave. It is because of this accessibility to the demographic he fetishized, the lack of protection and other factors, such as the AIDS scare, that Dahmer was able to carry on his murderous and cannibalistic behavior for so long. It would seem that even if police offers were doing their jobs, many in the community would chalk up those missing as having moved, got sick or died.

Similarly, while also not ruled a hate crime, consider the Atlanta Child Murders from 1978-1981. Within just a few years’ time, 29 Black children, teens, and young adults were kidnapped and murdered. While Wayne Bertram Williams would be convicted for two of the murders in 1982, justice wouldn’t be seen until more attention about the ongoings was brought to light by the Black community, causing then-Georgia Senator Sam Nunn to request the Department of Justice to permit FBI involvement.

So, were local police officers working diligently to find these missing children prior? Just as the ones in Milwaukee were searching for missing, young, marginalized men in their own communities? Or had everyone just vanished?

Some texts on the Dahmer cases, such as in Anne Schwartz’s The Man Who Could Not Kill Enough, favor the city’s police work—particularly regarding the night encounter with Konerak Sinthasomphon. In her report, Schwartz proclaims that the cop duo was respecting the gay couple by letting Sinthasomphon go back to the apartment with Dahmer.

In opposition to her opinion, had police run his name, they would have known that Dahmer had a prior offense on record, one that he got involving Sinthasomphon’s older brother. Instead, she focuses on Dahmer’s own victims’ criminal records as if to insinuate that gay people, or anyone with a criminal record, deserve death.

In both current cases and in the cases of Dahmer’s victims, these members of the community will be profiled and demonized to better serve the “protectors” of said community.

Did We Really Need Another Dahmer Movie?

Did we really need another movie, TV show, or otherwise about Jeffery Dahmer, right now—or ever? As mentioned before, 14 retellings of the serial killer’s stories have been released in the last three decades. Four of which have occurred in the last three years.

While I was a fan of My Friend Dahmer, both the comic book and the film, I thought that it had been a unique take on Dahmer without causing the retraumatization of victims’ families—or at least not as much as others. And even if there was more to learn from Dahmer’s story, why not take a more traditional route like in Conversations With a Killer: The Jeffery Dahmer Tapes? Though this was released on Netflix after Murphy’s series, I saw the escalation in coverage and disregard for the victims’ families as salt in an already reopened wound.

I can’t disagree that Evan Peters portrayed a very convincing, strange, and scary Dahmer, or that the film style and pace were unsettling—or anxiety-inducing. The fact of the matter always was that he killed people. We were shown how he might have killed those people, and with great detail pertaining to their personalities and scenes of death.

I can’t speak to if his childhood or his abandonment issues are what led him to be able to dehumanize these individuals so that he could keep them forever by means of strangulation or amateur lobotomy—self-taught taxidermy and cannibalism—but I do realize that instead of exploring that dehumanization in Monster, the series attempts to humanize Dahmer instead.

It did not really give us a story told through the eyes of the victims, but just enough context to keep us on edge, eager to learn something about where they might have gone wrong. Waiting for Jeffrey's capture and conviction. In terms of where we were hooked, Vicary hit the nail on the head.

Going back to Golub’s point, though, in order to really learn something from this, for every viewer to get something out of this new retelling, is to figure out ways that it connected to society’s fears, anxieties, violence, and coping. Just as a woman might feel anxiety or fear about walking home alone at night, we need to see what Dahmer’s victims may have feared and what those people still fear today.

For all the strides we’ve made in current society, gay rights are still on the ballot. Hate crimes against the demographic still occur, and there is an ongoing fight for the rights of trans kids. Black and Indigenous communities are still marginalized and victims of police brutality on a regular basis. If anything, Monster could have been a series that shed light on those still present fears and anxieties instead of perpetuating violence.

From this point, what do we do with the information? Is it actually absorbed or just made into another meme, a TikTok video, or more recently, a Halloween costume? Does that aftermath balance what we’ve learned, or does it take things over the edge? We can't ignore how several victims’ families didn’t know about the series, and how others were portrayed practically scene-for-scene and word-for-word during one of the court hearings without even being contacted.

The re-traumatization and exploitation of these people are hard to put a price on for the sake of entertainment, or at its utmost length, education. While there is much to be learned, I’m not sure we are all absorbing it in a way that could better the future. I’m not sure how many times the world can have us look at a killer in a different light. The fact of the matter always is, it's not about the one who took those lives, but the lives that were taken.

Article written by Destiny Johnson

Destiny writes about true crime and thrillers. She mostly enjoys movies and stories that cause one to question the world around them.

![Letters To The Purple Satin Killer [Book Review]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1737827737735-EBFQ2I9BEDMC4HTPK5ZJ/purple-satin-killers-cover.jpg)

If you’re someone who frequents oddities or metaphysical shops (hell, even antique shops in some instances), you start to get pretty good at sensing the authenticity of not just the items around you but the people, too. You’re able to distinguish whether or not those standing behind the counter love the stuff as much as you or if they’re in it for some other reason, be it money, fad, or something else.