The Entity: Trauma and the Transgression of Spirits, Part III

Before reading this essay, I highly suggest reading Part I and Part II of the series, which introduce the plot and characters of Sidney Furie’s The Entity (1982), as well as serving to begin breaking the film down into its themes, such as the male identification with a female survivor of sexual assault and the male-centric bias of psychoanalysis. In this essay, I want to continue where we left off—that while the conclusions of the panel of psychiatrists diagnosing Carla were faulty and based broadly on their discriminatory perceptions of the patient, the filmic language itself offers some (potentially) redeeming evidence for the doctors that could support their diagnosis.

The Significance of Mirrors

After one of her attacks, midway through the film, Carla goes around her bedroom, breaking every mirror in the room. On its own, this rage is easy to justify. She’s tired, frustrated, and angry—at the entity, of course, but also at herself. Up until this point, she had thought she had been doing everything right. She had the support of her children, of her best friend, and of her doctor, who assured her that he had her on the path to serenity. When that illusion is broken, she lashes out. But taken in the context of film as a medium, Carla’s breaking of the mirrors in her fit of anger, or rather, the presence and placement of mirrors throughout the film, serves a purpose that can be read as favoring the doctors’ diagnosis.

The mirror is one of the most frequently used symbolic objects in the language of film, used to convey anything from a moment of self-reflection to a duality or underlying duplicity of a character, and, considering the frequency with which they appear, their usage in The Entity cannot be ignored. Carla’s first assault, for instance, happens as she’s brushing her hair, sitting with her back to her vanity mirror, suggesting a truth she refuses to acknowledge. This idea of a hidden knowledge resurfaces later in the film, but the significance here, during the first attack, is that it is the first time that Carla has had to confront the potentially disturbing things in the back of her mind.

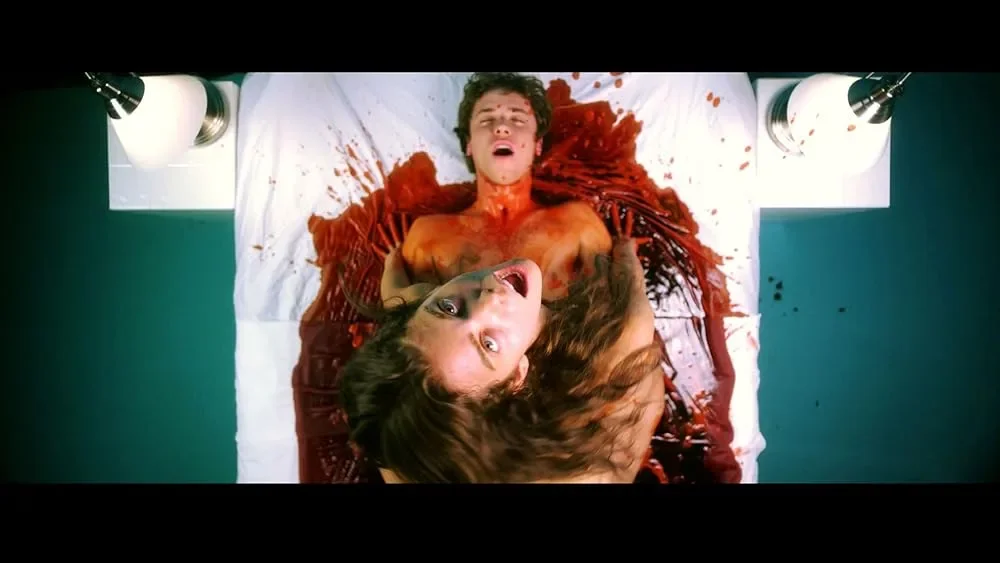

The Entity, 1982

In the very next scene, we jump to the second attack, again taking place in the bedroom and involving the vanity, but this time adding a mirror atop Carla’s dresser. As the furniture in the room shakes and rattles, the camera alternates between these two mirrors, offering us both reflection shots and point-of-view shots, putting the audience in the position of both “gazer” and “gazed upon.” Carla escapes with the kids, but when she runs back into the house to retrieve the car keys, our view is limited again, almost entirely, to reflections in mirrors around the house.

Two things are taking place in this scene. First, by alternating between the points of view in the bedroom, the viewer is allowed to become complicit in Carla’s terror, without fully releasing her own point of view. From Carla’s position on the bed, our focus is drawn to the mirror, which is placed high in the room, able to see everything else—Carla, in particular. We are acutely aware that we are being watched, but there’s nothing we can do. But then the perspective shifts and we are instead the ones doing the watching. We see Carla in the reflection of the mirror as she sits in bed, frozen with fear. This distance brings us back to a position of strength, emphasizing the power dynamic playing out and further arresting any ideas we may have that we might do better.

Notably, as the kids cry in the backseat, Carla grills Billy. “Did you hear it?” she shouts. “Hear what?” is his reply. In an intense, confusing situation, she’s already unwittingly planted the seeds of what her children have experienced in their heads for them. Later, when the panel of psychiatrists are discussing her case, they pick up on the same: “Hysteria is contagious,” Dr. Weber says, “given the right circumstances, anyone can see and feel things that simply aren’t there. And the children are just supporting mama’s delusion.” Later, after the living room assault, Dr. Sneiderman admonishes Billy not to feed into his mother’s delusion:

“Billy, look, would you do me a favor? Don’t pretend next time. The next time your mother thinks she sees something or she hears something, she wants you to corroborate it. And when you do it’s that much more difficult to convince her that it’s all in her head, it’s a delusion.”

“I didn’t get a broken arm by pretending,” Billy says, sidestepping the fact that his injury happened during the very real fall he took during the attack—not necessarily by any paranormal intervention. Further to this point, in a draft of the script (DeFelitta), Bill instructs his sisters to help him fend off Carla’s attacker, in a way that reads suspiciously like pantomime. “Kim! Julie! Help me fight him off! Hit him! That’s it! We’re getting him! He’s leaving!” Whether intentionally or not, one could argue that Billy is doing what Dr. Sneiderman fears he is.

The Entity, image modified by author. Click to zoom.

When Carla readies her bath before the third attack, mirrors play yet a bigger role. Before undressing, she stares through a tri-view mirror, directly into the camera, as if implicating the audience in the violence we are about to witness. The three panes of the tri-view can represent a number of things: a fractured psyche, an unresolved decision, competing personas. For Carla, the two flanking reflections stare back at Carla’s center. As was the case earlier, she is still not using her mirror to look at herself, but deflecting by looking at us, the viewers. This time, however, her reflection isn’t so easily diverted, as her internal conflict is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

As the doors to the bathroom swing shut, Carla puts her back to the full-length mirror on one of the closed doors. Once again, she puts herself in a defensive position, looking out and away from any introspection until she is forced, literally, into the mirror over the sink as the entity shoves itself upon her. Over the course of the scene, Carla is forcibly thrown between accepting and denying her childhood trauma and the effect it is having on her as a mother.

When Sneiderman takes Carla home from the clinic, they have a discussion in the bedroom where the first two attacks took place. Once again, Carla spends the entire scene in front of, but facing away from a mirror, but even more explicitly, their conversation is shot almost exclusively with both Carla and Sneiderman’s reflection behind her in frame. Sneiderman is the one facing Carla’s own reflection, not her, as if he is already more attuned to her traumatic history than she is. Sure enough, it’s immediately after this that she admits to Sneiderman that her father had abused her as a child.

At last, we can return to the attack that causes Carla’s rage. Until this point, the entity has been physically and emotionally terrorizing Carla, but it is this one, the fifth on-screen, that we see the most psychological damage being done. Rather than seizing her limbs or slamming her against a wall, the entity waits until Carla is asleep. Before she realizes what is happening to her, Carla awakens on the verge of orgasm, throwing her into the inconsolable fury that causes Billy to run into the room, and leading Carla—for the first and only time in the film—to scream at him: “Get out!” Carla’s shame in this scene is the first open indication of her incestuous thoughts.

As I had introduced in the previous article, the original script made this scene much more explicit in its intent. However, not wanting to draw too deeply from the draft, I’d like to instead emphasize what actually appears in the final cut, as there is plenty enough evidence, though subtler, to come to a similar reading, while also making for a better film. When Carla shouts at Billy, she isn’t angry at him so much as she is at herself for the thoughts she’s had that she refuses to admit—hence her breaking of every image of herself in her room. Contrary to the many scenes in which she turns away from mirrors, though, her violent reaction implies an acknowledgement of the thoughts, confirming the conclusions that, to this point, are known only to the audience and Carla’s team of psychiatrists at the clinic.

Because there is such clear and consistent imagery throughout the text, and because it permeates it so completely, it is impossible to disregard it as a coincidental or stylistic choice. Though the film intentionally frames the narrative from Carla’s point of view, thereby engaging the audience from the start with how Carla understands the attacks to have taken place, it uses these nondiegetic clues to hint at the credibility of the doctors’ conclusions. But while this adds a great deal of texture to the plot, I don’t want to imply that it excuses the facts as discussed in Part II of this series—that the doctors, unaware as they are of the artistic decisions of the filmmakers, make their assertions by ignoring Carla’s own experiences, and without first considering more serious physiological causes of her episodes or referring her to a hospital for evaluation.

It’s my belief that, while the film never abandons Carla’s point of view, Furie and cinematographer Stephen H. Burum use this imagery, not to discredit Carla or the paranormal nature of her attacker, but to nod to the credibility of the doctors’ opinions. Both can be true, but ultimately, it’s a question that evades the point—that even in the face of overwhelming physical evidence of abuse, the medical establishment failed to take seriously the testimony of their female patient. Even supposing everything they assume about Carla and her past is true, their treatment does nothing to prevent the real, tangible trauma that she is experiencing in the present. When Carla realizes this, she is more than happy to run into the welcome arms of the parapsychologists, which will be the focus of the next installment of this series.

References

DeFelitta, Frank. The Entity. 25 Sept. 1978. Horror Scripts and Ephemera Collection. SC.2019.04, Box 1, FF 22. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Article written by Ande Thomas

Ande loves the intersection of sci-fi and horror, where our understanding of the natural world clashes with our fear of the new and unknown. He writes about monsters and foreign horror and can also be found over on Letterboxd.

Bones and roots adorn the walls of their dimly lit home. A mjölnir necklace hangs around K.’s neck as he hand carves incense into a small cauldron burner and a breathy soundtrack begins to play. This is a couple that is in tune—with themselves, with the natural world, and, as we will soon see, the supernatural world, as well.