The Haunted Spaces of Suburbia: An Interview with Robert McLaughlin

Hauntings are not restricted to the dead: economic, social, cultural factors, and the very past itself can come to bear on the present—silent, “invisible” forces that permeate and influence our very reality. Hauntology, a concept coined by philosopher Jacques Derrida in his 1993 work Specters of Marx, delves into these ideas, as well as the concept of lost futures that never arrived.

According to Robert McLaughlin, lecturer in film at Birmingham City University, “[hauntology is] “how the ‘suburban uncanny’ is mirrored in the ’50s, ’80s, and in the present resurgence of hauntology, and how safe spaces and of a potential 'modern' idealized future become places of unsafe decay and of the horrific.” McLaughlin is also the author of a book on Poltergeist for Auteur Publishing. In his research, he examines how horror often returns to the suburbs during conservative times.

McLaughlin, who has been teaching for roughly 15 years, has created content for Den of Geek, Sequart, and World Geekly News. He also works with Professor Xavier Mendik as one of the directors of the Cine-Excess festival, and serves in project management for two events at the university. In addition, he works with television archivists Kaleidoscope on a quarterly event that focuses on lost or forgotten television, among other projects.

What initially drew you to study and teach film? What drew you to horror?

I have been working as a lecturer for just over a decade teaching film industry and context; however, the conversation with undergraduate film studies and filmmaking students in tutorials scenarios has always seemed to return to the theme of horror and horror films. It is the theme that, no matter how long the budget, how trashy the production values, or how unconvincing the monster is, a genre film that is universally liked by the majority of my student cohorts for the past few years.

The personal interest in horror comes from a fascination as a child with monsters—whether it was books on mythology, folklore, or reading the abundance of not particularly child-suitable supernatural books that appeared in the late 1970s such as the Usborne Supernatural Guides series, which were a pocket-sized range of books that were dedicated to highlighting the world of the “supernatural.” One was titled Vampires, Werewolves & Demons. (These were far too gory for children.) Essentially anything that had creatures in them. British comics, Doctor Who, or the continual reruns of Ray Harryhausen films that played on every public holiday.

The notion of monsters and the monstrous used to fascinate me and led to an eventual further interest in creature features, folk, and horror films that were available to watch thanks to the prevalence of VHS video in the U.K. during the 1980s. I tried to watch everything I could from relatively harmless giant bug 1950s creature features, but “thanks” to lapse hiring policies and liberal parents, I saw things that more than likely I shouldn’t have, and got a very quick schooling thanks to the likes of Zuni dolls, Shadmocks, and Manitous that all caused more than a few nightmares. Staying with my interest in literature, books, and research, I studied humanities at school and did a degree (way back in the 1990s) in marketing and design, where I focused on copywriting.

This “geekery” led to various creative jobs, and eventually to a role where I was sub-editing a collectible and model magazine as well as writing articles (reviews, critiques, covering cons, and writing news pieces), and in a roundabout way that led me to education and to teaching film and film studies—not knowing initially that there was as entire subculture of academia that dealt with horror.

Have teaching and working on projects like Den of Geek been largely complementary endeavors, or have they each provided their own challenges? Has Den of Geek and other similar work inspired the direction of your research in any way?

Yes, working for commercial websites such as Den of Geek, Sequart, and others has complimented my academic work to no end. A germ of an idea can be developed through initial research and developed into a commercially focused 600- to 1,000-word article aimed for a “wider” audience, either on a website or to go to print. These ideas then sometimes germinate into a niche and academically driven piece that is then submitted as a paper for a journal or used as part of a lecture series. An entire lecture came from a potential (rejected) article that looked at the 1970s and went from Easy Rider to Smokey and the Bandit—this eventually became an entire lecture based on “road movies” and the changing social landscape of America in the 1970s.

These ideas, articles, and proto-papers are a good way to allow for personal review, reflection, and to allow my writing voice to tell a story and to create a structure of an initial draft without the need for academic citation. I have always written on subjects that interest me or topics that I am happy to research about. The nice thing about sites like Film Stories and Den of Geek was that editors (especially Simon Brew) allowed for a range of topics or themes to be written about. If an article fit into the remit of something “geeky,” it was considered for publication. (I am currently halfway through a “100 years of horror” article.)

Where did your interest in hauntology start?

I think my interest in hauntology started as a general interest in forgotten things and half-remembered television programmes and films, and their association with childhood and growing up—a sense of peculiarity that permeated the U.K. in the 1970s and 1980s. Up until a couple of years ago, I did not know that hauntology was a term that existed to describe this notion, or that there was even an entire avenue of creative and academic research looking into the subject.

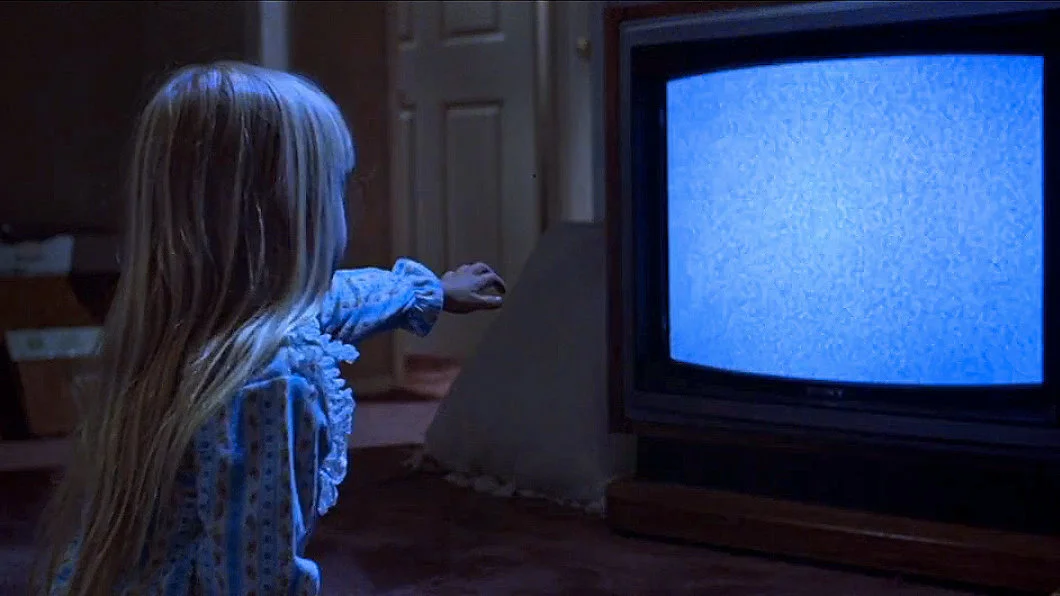

Image courtesy Rob McLaughlin

I was born in the mid-1970s in the U.K., which, at the time, was going through a period of recession, strikes, and social unrest. As such, things were quite rundown and tatty—socially frayed at the edges, especially smaller towns where I grew up that had been “forgotten.” Having memories of rundown tower blocks (built only a decade before), abandoned houses, and patches of hugely unsafe wasteland mixed with seeing riots on television, punk, and an anarchy in music and what was broadcast, mixed with other more esoteric things that were shown on television—like writers such as Nigel Kneale and Richard Carpenter—made this an odd time to grow up. The notion of a haunted Britain was prevalent in music, film, and television, as shows such as Bagpuss, Children of the Stones, Worzel Gummidge, and a lot of adaptations of E. Nesbit books were broadcast to children, which all had this weird, haunted folklore feel to them.

[I also sat] in front of a television during cold, dark winters with this diet of show after show highlighting British myths and folklore mixed together with the continual public information adverts that ran on television during this time. For those who have never seen these adverts, they were very much like the “Duck and Cover” adverts from the U.S. in the 1950s; however, [the U.K. adverts] were much more visceral and nightmarish. They were designed to stop the general public (especially children) from doing certain dangerous things, highlighting issues such as playing with fireworks in the street, using construction sites as playgrounds, and the dangers of electricity pylons—all of which did not shy away from showing the graphic detail of the child who was burnt, buried, or electrocuted.

Two of these public information films are particularly disturbing. One of these is the incredibly creepy: Lonely Water (1971), a short film about the dangers of children playing in or around riverbanks, lakes, or bodies of water. It was narrated by Donald Pleasance and had the same feel of a British Grindhouse horror, and has to be watched to be believed. (It’s on Youtube.) These are the basis for the dystopian hauntology of Scarfolk. The other nightmare-inducing public information broadcast was a short film that was shown in schools called Apaches (1977), in which schoolchildren come to some very gruesome ends while visiting a farm due to reckless behaviour. (One falls into a slurry pit, one gets poisoned, and one gets crushed.) As you can see, the foundations of a lot of British children’s—mainly those who were born in the 1970s—formative years were pretty dark. There had been some fantastic parodies of the 1970s and 1980s on television that really captured the feeling of this, such as BBC’s Look Around You (2002), which really had the perfect tone of 1970s children’s education programming, to Channel 4’s Garth Marenghi Darkplace (2004).

Reading websites like Richard Littler’s Scarfolk, I realised that there were other people who also went though that sense of unease as a child and had translated that into other creative channels, and who perfectly captured the design aesthetic of the time. It was then with the Bob Fischer article in 2017 for Fortean Times that really resonated the same feelings of nostalgia and “oddness” that this era of growing up brought about.

While researching hauntology a little further, I found that it was a phrase that was developed by philosopher Jacques Derrida within his text Spectres of Marx and initially phrased to define “temporal and historical disjunction” in the context of the disjunction of social expressions of ideas, art, creativity, and culture. This perfectly sums up the notion of hauntology as an attempt to find the appropriate signs/signifiers or symbolic expressions of the meaning of experiences of these promised and lost “modern” futures.

Hauntology, however, described by Bob Fischer, can be simply summed up in two short, but very effective descriptions: It is the “nostalgia for a lost future” or the research into “post-modern antiques,” both of which are a little less verbose and a bit more user-friendly.

Could you provide additional detail about the research you're currently working on?

As part of my remit at work, I work very closely with the television and film industry, especially in the areas of television archiving and the idea of digital heritage, to which the theme of hauntology as an area of research fit perfectly. Rummaging through old boxes of tapes, cans of film, magazines, periodicals, books, and ephemera from the time is a perfect tactile way of connecting with those feelings of nostalgia (especially when books have that old book smell).

Our university department has a very strong relationship with independent television archivists Kaleidoscope. As an internationally recognised body, they work very closely with the British Film Institute on a set of events called “Missing, Believed Wiped.” Up here in Birmingham, at Birmingham City University, the team and I put on events that showcase lost, forgotten or niche themes. Over the years we have put on events that have covered lost music on television, which highlighted and showed some unseen Beatles footage, as well as some fantastic events based on children’s television, drama, science fiction, and live broadcasts. Over the past academic year, we have also hosted a fantastic event that celebrated 50 years of colourized television.

Other events have allowed me to speak to international guests, such as ex-Bond girl Maddie Smith, Louise Gold (one of the original puppeteers from The Muppet Show), Francois Pascal (star of early Norman J. Warren films), writers, directors, and producers, as well as becoming close friends with the writer of Event Horizon (Simon Weitzman). These events have also led to collaborations with the BBC and potential endeavours with Netflix on a proposed documentary. This resource of industry practitioners, archivists, and experts is fantastic, and has allowed me to gain interviews, experiences, and primary resources that have become a personal mini-archive on all things geeky, cult, or weird from the 1970s and early 1980s.

What inspired the use of Spielberg as a lens to examine the connection with conservatism during the early 1980s?

Watching films like E.T. and Poltergeist (a bit of a mistake there) as a child, I was instilled with a fascination with America in the 1980s, which I have visited many times. I still have vivid memories of wanting to go and play Dungeon and Dragons with Elliot's family and eating Reese’s Pieces in big houses in California. When John Atkinson at Auteur Publishing gave me the commission to write the book on Poltergeist, I spent time building on these memories, and while initially this was a fantastic research exercise in nostalgia, the more reading I did, the more the veneer of the glamour of the 1980s (especially the politics) was scratched off.

Poltergeist

The Spielbergian “Suburban Trilogy” (Close Encounters, E.T., and Poltergeist) all provided viewers with a sense of overwhelming child-like wonderment, while at the same time underpinning these positive feelings with a tangible sense of dread and foreboding, a pseudo Americanized hauntology if you will. This is more prevalent in Poltergeist than any of his other films. The environment in which the Freeling children in Poltergeist live is “perfect” and very Spielbergian, a sanitized version of suburbia that Spielberg loved to represent. [This] harkens back to the stereotypical 1950s small-town American aesthetic—what is shown in Norman Rockwell paintings. And, of course, films like Grease, and in Spielberg’s long-time friend George Lucas’ underrated American Graffiti and his own Amazing Stories. Poltergeist is a perfect representation of the early 1980s, with the growing middle class (and an aspiration for British children brought up in the slightly more grimy ex-industrial towns of the Midlands). However, it is also a very good example of the representation of the growth of conservatism and the return to “traditional” values of home and self-improvement of 1980s political thinking. This is especially connected to Ronald Reagan's presidency. Reagan’s laissez-faire attitude of “free economics” and the weakening of regulation presented a supposed environment of enterprise, expansion, and profit, which, of course, led to the “greed is good” mentality of the 1980s (and eventual economic crash).

It is this insatiable “need to need” that feeds the notion of commercialism that is so relevant in 1980s culture. It is this consumerism and drive to want the underpinning soul-destroying qualities of the perfect suburbia in which they live—an innate focus on striving for a perfect lifestyle that will never quite be perfect enough. It is with throwaway lines of the text such as Carol-Anne’s innocent line of: “Oh well. Can I get a goldfish?” that Hooper and Spielberg can highlight the lack of appreciation for the material. Products, consumables, and even life itself are replaceable and hold no value to a generation bought up by the comforts of material wealth that middle-class suburbia provides and intends to aspire towards—essentially the same middle-class “vanilla” ordinariness of the Freelings themselves.

Writing about Poltergeist in terms of the social and political context of the time allowed me to explore how the buy/consume/dispose mentality of the 1980s came, and how in the text these themes come to represent the very epitome of consumerism distilled into one family environment and within. The Freelings present this mindset, and one in which all other values are relegated “value” (family, love, mindfulness, and contentment) as secondary concern, for which, of course, the spirits within the film “punish” the family (by abducting Carol-Anne) and from which the family learns and as such, emotionally evolves.

Having Tobe Hooper direct the film I think enhances the film greatly, and as such provides Poltergeist with the needed satire of consumerism—a feeling that in my research is evident in Hooper’s own opinion as a counter-culture and liberal thinker.

What, to you, are the largest differences between, as you described, the "British Scarfolkian take" and Fischerian hauntology? Do you think Fischer's direction with hauntology influences horror or will in the future?

Bob Fischer’s articles (and subsequent work) have quite a light-hearted tone. He mixed the folk, oddness, and nostalgia with a genteel Britishness, which is found in television shows such as Last of the Summer’s Wine. It’s reminiscent, but through a certain lens of comfort and safety. However, my research seems to be noting there are varying themes appearing in hauntology, and a few distinct subgroups appearing in the genre.

As well as the rose-tinted reminiscence of the summers of the 1970s—the summer of 1976 is still the hottest summer in the U.K. ever recorded—that Fischer looks at, there are some elements of British hauntology that come a lot more from social trauma and unrest, as well as an attempt to harness prior “good old days”/nostalgia.

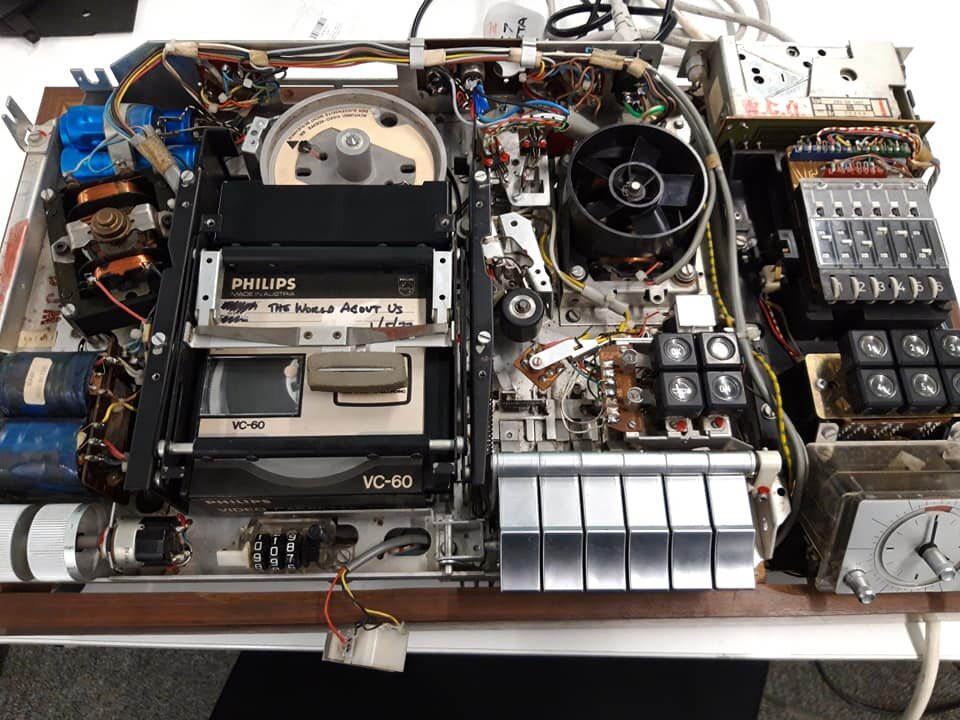

Image courtesy Rob McLaughlin

For all its folklore and mythology and the perennial themes of the beauty of the countryside found in English poetry, it still does rain a lot in the U.K., and added to the heavy industry still prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s, living in the U.K. was actually quite dour, and a lot of what was presented on television, such as Grange Hill, Coronation Street, Alan Bennett talking-head monologues, and a lot of the social realism drama on television, as well as in music and art, gave hauntology a gritty realism—a sort of “kitchen sink” hauntology. Taking this discussion and theme even further, the post-apocalyptic or presentation of Britishness via a dystopian representation of social issues, as seen in television shows such as Quatermass or Threads, provide a framing of “dystopian” hauntology of high-rise flats and of darkened concrete and decay. These are all very Mega-City One, and is described in detail in Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. I have recently read a horror film script that perfectly sums this up a treatment that was a mix of Cathy Come Home and Soylent Green.

Other areas of investigation have shown hauntology contextualised as forgotten or disposed technology—whether that is the demise of the video shop, to more recently the virtual ghost-town of forgotten MMORPGs, to television shows such as Tomorrow’s World (a BBC show that ran from the 1960s to the late 90s), which looked at what technology was being developed but for whatever reason was passed by or forgotten (video 2000, minidiscs, UMBs, etc). This could be seen as “technified” hauntology, which has been described as current digital technologies can be “haunted by their analogue counterparts.”

Other areas are the “folkloric” hauntology, “paranormal” hauntology (Arthur C. Clarke and Osbourne books, for example), or American hauntology—the dream of the white picket fences, Main Street USA, and eventually Googie-inspired Jetsons-like futures that never came to fruition. The more that is developed in this era or retro, nostalgia (and even the nostalgia of nostalgia) with remixes, remakes, and reworking, I feel that that hauntological themes will influence horror and cult media even more than they are now.

What inspired the course of your current research? What are your next steps for this work? Do you have any other research projects planned for the near future?

Research-wise I have been asked by our school lead to potentially set up a hauntology research cluster. As an evolving area of social, political, and digital heritage, there is potential for conferences and papers that can be framed by hauntology. While this may well be down the line research-wise, I have also signed a new book contract looking into this area, as well as working closely with Kaleidoscope on a couple of projects. I am also editing some papers in Gothic fiction and looking at a final edit for a colleague’s monograph, so I have presently a lot of fascinating, eerie, and odd things to get my teeth stuck into (as well as the usual cycle of university marking, preparation, and delivery).

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview by Laura Kemmerer

Laura tuned into horror with an interest in what these movies and books can tell us about ourselves and what societies fear. She is most interested in horror focused around the supernatural, folklore, the occult, Gothic themes, haunted media, landscape as a character, and hauntology (focusing on lost or broken futures).

Throughout the decades, slasher film villains have had their fair share of bizarre motivations for committing violence. In Jamie Langlands’s The R.I.P Man, killer Alden Pick gathers the teeth of his victims to put in his own toothless mouth in deference to an obscure medieval Italian clan of misfits.