Immersed in Grizzly Bear Country: My Trip to Alberta After Reading ‘Mauled’

As I sit in the Bozeman-Yellowstone International Airport awaiting my flight home, I can’t help but be overwhelmed by all the wonderful sights and places I was able to experience during my vacation. While I could write a book about the scenery and paths traveled through Glacier, Yellowstone, and Grand Teton National Parks, the day trip I want to focus on for this article is the drive we took into Banff on Monday, July 29.

This is the first installation of a multi-post series focused on both true and fictional bear attacks and their relation to animal horror cinema. Given this exploration, please be wary of spoilers and gruesome details.

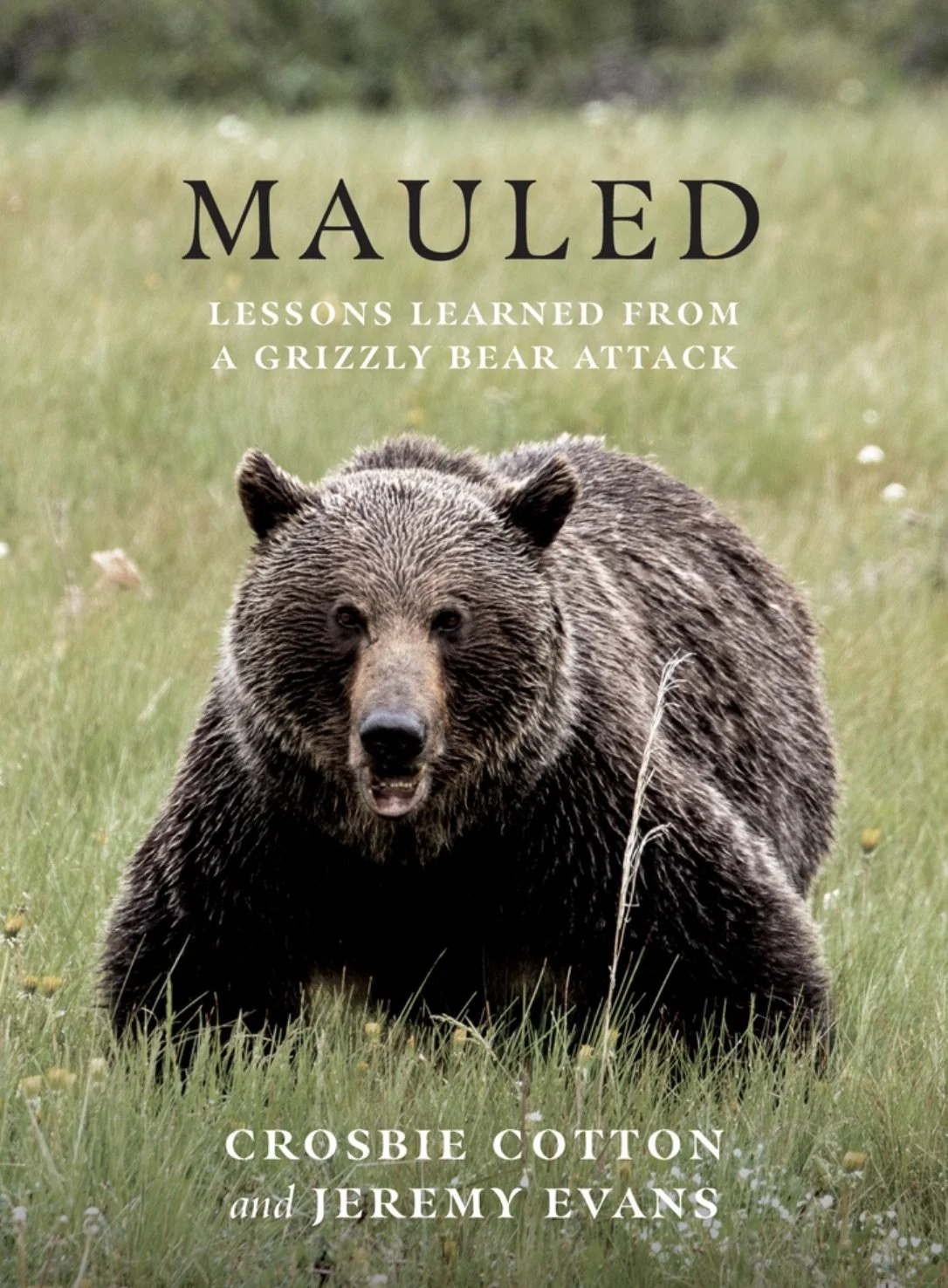

Leaving Pennsylvania’s Appalachia views for the Rocky Mountains of the West, I was eager to finally begin reading Crosbie Cotton and Jeremy Evans’ Mauled: Lessons Learned From A Grizzly Bear Attack. I ordered the book just days (maybe even hours) after listening to National Park After Dark’s interview with Jeremy Evans—to say I was intrigued is an understatement. The podcast episode was probably the first to make my stomach twist into knots and flood my mind with dread during my commute home from work. Something about both Jeremy’s horrific encounter and the positive outlook it has left him with is truly amazing and inspired me to get as many details as I could about the attack, grizzly bears as a species, and ultimately, how factual encounters such as these might have an impact on animal horror cinema.

When driving from St. Mary, Montana to Banff, instead of staying on Highway 22, we added an additional hour to our already four-and-a-half-hour trip to drive along Township Road 100A and Highway 40. While the detour may have prevented our already slim chances of being able to explore Banff National Park, it took us along backcountry roads passing notable Canadian Provincial Parks: Height of the Rockies; Peter Lougheed; Elbow-Sheep Wildland; and Spray Valley, also known as Kananaskis Country. Looking back on it now, while I was skeptical of the route taken during our venture, the sights and roads less traveled proved equally exciting and the perfect setting for my research. On both sides of the truck we were surrounded by towering, jagged mountains composed of layered sedimentary rocks such as limestone and shale (Adventures.com) that were covered in thick pines, lining the massive landscapes up to roughly 7,500 feet in elevation where the terrain and altitude would eventually prevent their growth (nathab.com). The thought of being lost in this wilderness planted an eerie feeling inside my mind as everyone expressed their wonder and awe of the backcountry we kept driving deeper and deeper into.

In the retelling of Jeremy’s attack, the writers described how his location at the time of the mauling was truly remote, having been more than a dozen miles away from where he parked his truck—deep in the backcountry of the North Burnt Timber drainage (Cotton, Evans 25). This would be another 156 kilometers away from where we had made it to Banff since no route goes over Mount Costigan. Although I would never make it quite as far as Jeremy had, driving the backroads along the same Canadian Rocky Mountain range and watching from the truck as several fishermen headed down to the nearby rivers by themselves still managed to send a chill down my spine.

Described by National Park After Dark hosts Danielle and Casey, (NPAD 136 00:01:27) and by others in his book (Cotton and Evans 12) as an experienced outdoorsman, Jeremy was right back out just days after leaving the hospital (134) despite his near-death encounter. Always hiking and biking through the backcountry scoping out his next hunting spot, Jeremy is no stranger to the area where his attack took place. However, if we’ve learned anything from his story or others like it—fact or fiction—no matter how comfortable a person might be in the woods, their safety is never guaranteed. Looking back at prior articles and recent events, this can be said for the Missinaibi Provincial Park incident that inspired Adam MacDonald’s Backcountry, or even more recently, the Massachusetts hiker who was attacked in The Grand Tetons National Park. News outlets and history will tell us that grizzly bear attacks, although rare, are not uncommon along the North American Rockies (Worldmetrics.org). And although there are plenty of proactive measures we can take to protect and defend ourselves in the event of an attack, our survival still isn’t one that’s promised. This is partially because not every grizzly bear attack is the same, and not in the sense of who is being attacked or where, but why.

In the event of a grizzly bear attack, the animal is attacking either in defense, most commonly a mother protecting her cub(s)—as suggested by Regional Wildlife Specialist Todd Ponich in Jeremy’s case (Cotton and Evans 129)—or the pursuit is predatory, meaning that the bear sees you as prey. The latter is much more rare but does happen on occasion (IDA USA). Reading and listening to this information, consuming every detail of Jeremy’s attack, seeing the horrific selfie (Cotton and Evans Image #9) he took of his face after his encounter with the grizzly momma, and reading through the notes provided by his medical team on how his body was pieced back together, my stomach continued to twist.

In the introduction of Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History, and Criticism, editors Katarina Gregersdotter, Jöhan Hoglund, and Nicklas Hållén write:

On a very basic level, animal horror cinema tells the story of how a particular animal or animal species commits a transgression against humanity and then recounts the punishment the animal must suffer as a consequence. In this way, the horror that most animal horror cinema depicts turns on an attack on human beings by an animal. This is the case even in the many films where humans are to blame for this attack by first violating the territory of the animal or by controlling the animal.

It’s quite a spot-on observation that only a few paragraphs after this, the editors point out that, because in cinema the animal will exist beyond the ethical, like other characters in horror, it will be hardwired to be a relentless predator, giving humans the only option to kill or be killed (Gregersdotter et al. 7).

While Jeremy’s story hasn’t inspired a feature film (at least not yet), other victims’ stories certainly have. In these cinematic retellings—thinking Grizzly (1976) and The Revenant (2015), among others—and as if under some kind of pressure for entertainment, the grizzly bears are portrayed to be even more dangerous by looking much larger, stronger, and scarier. An exasperated Jaws-like tactic to make the animal even more terrifying, the reality of a grizzly attack, or any bear attack for that matter, will legitimately shake you to your core. So why then, do horror directors and filmmakers focusing on animal attacks need to check off this seemingly required box for their films to be arguably successful? Certainly, this is just one question of many that both the nonfiction book and several bear-attack horror films have left me to ponder.

While this article serves as the opening to this exploration, the question we must constantly ask ourselves in each observation of film is whether the animal, in this case, a grizzly, deserves to be punished, or killed, simply for being an animal within their natural habitat. In Mauled, rangers searched for Jeremy’s attacker, but she was never found. While Jeremy himself holds no remorse for his attacker, it is often believed that if a bear has a negative encounter with a human, its chances of happening again are increased (NPAD 111). To protect other people, especially in a predatory-type attack, the action is almost always to eliminate the threat—but is that really the right thing? Does one negative counter mean that all encounters will be negative or that the animal will go on a killing rampage? Each story is and will be different, but I encourage you to follow along as we dissect these findings in other works of bear-related animal horror cinema.

Works Cited

“The Canadian Rocky Mountains.” Adventures.com, adventures.com/canada/attractions/mountains/canadian-rockies/. Accessed July 2024.

“Know Before You Go: Geology & Ecology of the Canadian Rockies: Ecological Zones”. Natural Habitat Adventures, www.nathab.com/know-before-you-go/alaska-northern-adventures/canadian-rockies/geology-ecology/ecological-zones/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20treeline%20is%20around,higher%20as%20you%20travel%20south. Accessed July 2024.

Cotton, Crosbie, and Jeremy Evans. Mauled. Rocky Mountain Books Incorporated, 2022. Accessed July 2024.

National Park After Dark (NPAD) Podcast. Episode 136: Mauled with Jeremy Evans. Accessed August 2024.

King, Destiny. “Exploring Wilderness Horror in “Backcountry” (2014)” whatsleepsbeneath.com, www.whatsleepsbeneath.com/archive/backcountry. Accessed August 2024.

Bishop, Sydney. “Grizzly bear attack at Grand Teton National Park leaves man seriously injured” CNN.com, www.cnn.com/2024/05/21/us/grizzly-bear-attack-wyoming/index.html. Accessed August 2024.

National Park After Dark (NPAD) Podcast. Episode 111: Creatures of the Wild ft. Tooth & Claw Podcast. Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Accessed August 2024.

www.idausa.org/campaign/wild-animals-and-habitats/bear-attack/

Gregersdotter, Katarina, et al., editors. Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. Accessed July 2024.

Article by Destiny King

Destiny is a supporting member of the Horror Writers Association who’s been working in B2B publishing for nearly a decade. Her favorite horror subgenres are true crime, found footage, and psychological thrillers. Find her on Letterboxd.

To any external observer, some indifferent alien surveyor, it would be the insects who rule the planet known as Earth. They fill the gamut of ecological niches, from lowly grazer to apex predator. They’ve developed agriculture and architecture as well as less visible, but no less complex, social structures. They outnumber the planet’s dominant mammalian species, an amusingly recent development in its bio-history, by a factor of nearly 1.5 billion to one.