10 Years After ‘The Skin I Live In’: Abject, Object, and Gender

content warning: sexual assault, suicide

Pedro Almodóvar’s controversial 2011 film The Skin I Live In is the ultimate conundrum: It is beautifully shot, it has one of the finest scores I’ve heard, it’s exciting and shocking, and yet it is deeply problematic. As we celebrate the film’s 10-year anniversary, I want to attempt to reconcile its troubling subject matter with some of the work that inspired it, as well as the legacy it left behind. Doing so requires that I discuss the plot of both this movie and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960) in great detail, and with The Skin I Live In in particular, sensitive topics will be discussed, including sexual assault and suicide. I will also be treating the film as a text, referring to characters as they are in the film for the sake of clarity.

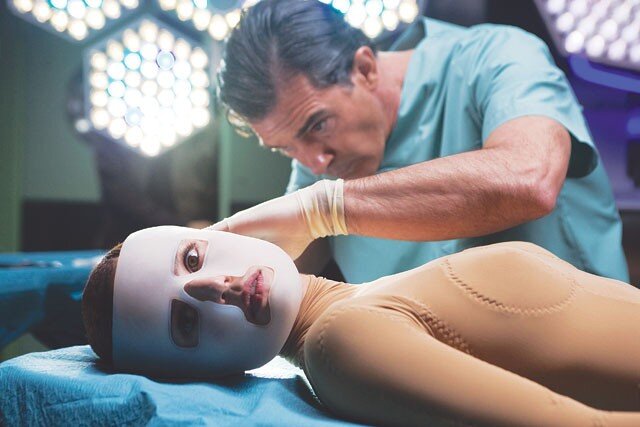

The Skin I Live In, image via IMDB

The Skin I Live In stars Antonio Banderas as Dr. Robert Ledgard, a cutting-edge plastic surgeon, and Elena Anaya as Vera, Robert’s live-in patient whom he keeps in a lavish (but locked) room in his villa in Toledo, Spain. In the early scenes, Almodóvar doesn’t make any attempts to mask the power dynamic at play—Vera is Robert’s property; she exists at his pleasure and, therefore, for ours. As Laura Mulvey writes in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, “...the conventions within which [film] has consciously evolved, portray[s] a hermetically sealed world which unwinds magically, indifferent to the presence of the audience, producing for them a sense of separation and playing on their voyeuristic fantasy” (9). Indeed, one of the first times we as an audience see Vera is through a screen-within-the-screen, as Robert gazes on her naked, lounging body on an enormous television screen. Vera’s image spans the wall like a living Renaissance painting. The comparison isn’t made in a vacuum—on the landing outside Vera’s room, full-size reproductions of Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Venus with an Organist and Cupid hang prominently. It’s a bit of symbolic overkill, but the inclusion of the paintings cements Vera’s role as objectified form, Robert’s position between the viewer and the television screen allowing him to stand in for the viewer, now free to gaze through Robert’s eyes. Only after he enters her room does Robert realize that Vera, whose body he had been admiring just moments before, had actually attempted suicide, her wrists meticulously slit with pages from a Cormac McCarthy novel.

A Father’s Guilt

In an alternate universe, The Skin I Live In could be a continuation of Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. Though the two films are adapted from two very different novels, the similarities that Almodóvar’s film has to Franju’s are difficult to miss. Robert, like Dr. Génessier in Eyes Without a Face, is a brilliant plastic surgeon obsessed with his craft, ethics be damned. In Génessier’s case, the patient is his daughter, Christiane, whose face was horribly burned in a car accident. In Skin, it is Robert’s late wife Gal who was disfigured. Christiane, like Gal, is forced to live in the total absence of mirrors. Both women are only able to get a glimpse of their injury in the reflection of an open window. The shock is enough to force Gal to throw herself out the same window, whereas in Eyes, it is one of Dr. Génessier’s victims, an unwilling donor for Christiane’s skin graft, that leaps from a window.

One key difference between the two is in their treatment of their female protagonists. While Almodóvar spends a great deal of effort constructing an altar of sexuality around Vera, dedicating large portions of the frame to her naked body on multiple occasions, Franju chooses to exhibit Christiane’s femininity in a much more subtle fashion. Her face seldom seen, and clothed in full-length, loose-fitting garments for much of the film, Edith Scob relies on delicate, graceful mannerisms in her performance as Christiane. She silently glides in and out of scenes like a faceless ghost, oftentimes watching the actions of other characters as if invisible. There’s a soft radiance to the character as we watch over the course of the film as, in an almost unspoken subplot, she loses all that binds her to this world. This distinction in how the films portray their characters is vital in understanding how Almodóvar handles the complicated subject matter of The Skin I Live In, which starts, first and foremost, with the largest divergence between the two stories—the motivations of the surgeons, themselves.

Dr. Génessier is compelled by the guilt of having been responsible for the accident that destroyed his daughter’s visage. The horror in that film comes from the obsessive control Génessier exhibits over his daughter in his apparent attempt to restore her life. Robert, meanwhile, is driven by vengeance, kidnapping and forcing a vaginoplasty onto his daughter Norma’s rapist, Vicente—to whom we are introduced as Vera. Complicating matters further, Vera, too, is raped by Gal’s ex-lover, Zeca, who mistakes Vera for Gal. Not only does Robert force sex reassignment surgery on Vicente, he follows it up with innumerable modifications to recreate Vera in his dead wife’s image.

It is with this revelation, nearly an hour into the film, that we see the true story begin to take shape. Until this point, the only clear villain has been Zeca, who shows up unexpectedly to the villa and is reluctantly admitted by his mother, Marilia, who has worked for Robert’s family for years. Zeca is on the run and intends to use his mother as cover for a few days, but as soon as he sees Vera on the security monitors, he ties Marilia to a chair and attacks Vera, before being found, and killed, by Robert. As they clean and cover up the murder, Marilia tells Vera about Zeca’s history with Robert and with Gal. Gal and Zeca were having an affair and planned to run off together when Zeca wrecked his car, leaving Gal to burn alive. Robert saved her life, but couldn’t save her skin, which haunts him to this day. That night, Vera, apparently grateful for Robert’s having saved her from Zeca, sleeps with him. As far as we can tell at this point, we are shown in microcosm a story of love and redemption—Robert, having failed to ultimately save his wife, has more success with her doppelgänger. The measures he had taken, the security, the surveillance, must have been an attempt to prevent a repeat of his wife’s fate.

Only now, as Robert and Vera lay in bed, are we sent back six years earlier and for the first time, learn about Norma’s rape at a party—first from Robert’s perspective, then from Vicente’s. Critically, the order of events as presented sets Vicente up as a victim, not an antagonist. Though he is in no way innocent, by acquainting the audience with Vera for the entire first half of the movie before even learning of Vicente’s existence, Almodóvar ensures that, in the context of the plot, his crime serves as little more than a pretext to give Robert an excuse to enact his sadistic fantasy. Having successfully kidnapped Vicente, Robert has a wide variety of tools at his disposal to enact his vengeance. Why then, does he choose what he does? Robert’s retribution seems to be less about bringing Vicente to justice and more about a twisted strategy to turn back the clock—to reconcile with his failure to save his wife.

Antonio Banderas and Elena Anaya in The Skin I Live In, image via IMDB

Gender as Monster

Rather than any sort of iteration on the rape-revenge genre, Almodóvar turns his attention toward the gender-as-monster trope, one that has its own long and problematic history in horror. From Psycho to Dressed to Kill and Deadly Blessing to Sleepaway Camp, Insidious 2 and House at the End of the Street, and many, many more, the genre has long used gender as a fairly cheap means to shock audiences. Ordinarily, gender-as-monster is used as a way to “explain” the villain’s crimes. In Dressed to Kill, the killer is the dissociated female personality of a man, subconsciously upset that he wouldn’t allow himself sex reassignment surgery. In both House at the End of the Street and Sleepaway Camp, the killers are revealed to have been abused by their guardians, who raised them as the opposite gender.

On a basic level, it’s easy to forgive writers for the trope—gender is one of the most fundamental aspects of our identities and so using it to otherize the antagonist is a trick that takes very little effort on the part of the writers. The horrifying consequence of this, however, is the way this otherization bleeds into the real world. Gender stereotypes, already a hot-button issue with so many, are so strongly reinforced by these fictional storylines that it is critical that writers and directors realize that by perpetuating these tropes, they do real harm to real people. In the context of The Skin I Live In though, things are a little more complicated.

Almodóvar attempts to use Vicente’s gender as a weapon against him and is the principal vehicle for driving our horror. Rather than revealing Vicente’s identity in the coda of the story, leaving audiences with a tantalizing shock ending as they exit the theater, its placement in the second act restructures gender-as-monster from derangement to punishment. On one level, this is good news. It avoids painting gender dysphoria as being responsible for the criminally insane. It also legitimizes the lived experience of transgender people, humanizing them by compelling cisgender viewers to watch in horror as a person is forced to occupy a body that is at fundamental odds with their internal identity. On the other hand, like those films before it, it uses gender as the foundation for a number of shocking revelations made throughout the film, firmly tapping—literally—into Freud’s “castration anxiety.” These conflicting ideas are at the root of the film’s tumultuous critical response, its legacy marred by its over-the-top use of the latter to attempt to achieve the former.

From the opening frames, as Almodóvar manipulates the audience into viewing Vera through Robert’s eyes, freeing us to objectify her with impunity, he maneuvers our expectations of Vera’s role in the world of the film. She is beautiful, mysterious, and hopelessly captive. We don’t know why she is a patient of Robert’s, or why she is under constant surveillance, but we are led to believe that it is related to her suicide attempt in the opening scene, rather than the other way around. When her identity is finally revealed to us, it snaps those events that preceded into focus, retroactively shocking us, not merely for the sadistic nature of Robert’s actions, but for our understanding of the relationship dynamic between him and Vera.

What’s challenging for this dynamic is how it seems to bow to the notion that to be female is inherently inferior to being male. This, of course, isn’t stated anywhere in the premise of the film, but the implication permeates it. As a male, Vicente has power. He is young, naive, and a lecher with clear problems with the concept of consent. Only as Vicente does he have the power to be the attacker. Only as Vicente is he in control of his situation. Vera, as a female, can only be attacked. Though she manages one escape attempt early on, she is quickly subdued by Robert, who never felt at any great risk. Only through Robert is she saved from Zeca and throughout the film, it is only through charm and seduction—passive methods of control—that she is ever able to gain the upper hand.

But Almodóvar uses the castration of Vicente as an active means of control—over the character and the audience. His manipulation of the audience into seeing the film through Robert’s eyes, and more importantly, seeing Vera through his eyes, Vera’s identity becomes all the more horrifying since we have been objectifying her from the very beginning of the film. Suddenly, we are acutely aware of the gaze we had been subjecting her to. Not only does Almodóvar make use of one of Mulvey’s avenues for avoiding the castration anxiety of the male gaze, that of fetishistic scopophilia, which “builds up the physical beauty of the object, transforming it into something satisfying in itself” (14) (by using the camera as previously discussed, in the first half of the film), but then actively leans in to that anxiety by literally castrating the object he worked to make satisfying.

Vera threatens to escape, The Skin I Live In, image via IMDB

By using Vicente’s gender as a weapon against him, Robert makes it clear that he means to assert total dominance over his victim and it is exactly this goal that is the most difficult part to swallow. For Almodóvar, “total dominance” means nothing less than the sexual relationship Robert attempts to initiate with Vera, ostensibly in an effort to replace the wife he lost, completing his cycle of revenge against Vicente, against Zeca, and against Gal herself. Though it’s possible that one could argue that it is by Vicente’s experience that people might be able to empathize with the feeling that your body is not your own, I strongly feel that the sadistic treatment of Vicente at the hands of Robert far outweighs any message about living with a mismatched sex. Rather than any coherent commentary, Almodóvar uses his subject matter—albeit effectively—to shock audiences into the plot twists, with the unfortunate side-effect of furthering the gender-as-monster trope in a way that only serves to reinforce prevailing stereotypes.

At its best, horror forces us to confront our demons and acknowledge those sides of ourselves and our societies that we’d rather be left unsaid. At its worst, it can unwittingly reinforce harmful ideas and stereotypes. Whenever filmmakers attempt to tackle social issues, especially within horror, they must take care not to allow it to devolve into spectacle. Though I believe The Skin I Live In is one such spectacle, it is still an exciting thriller, as long as you stay cognizant of the message it is sending, intentional or otherwise.

-

Eyes Without a Face. Directed by Georges Franju, Champs-Élysées Productions, 1960.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, Autumn 1975, pp. 6–18. web.english.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Mulvey_%20Visual%20Pleasure.pdf.

The Skin I Live In. Directed by Pedro Almodóvar, performances by Antonio Banderas and Elena Anaya, Warner Brothers, 2011.

Titian. Venus of Urbino. 1538. Uffizi Gallery, uffizi.it/en/artworks/venus-urbino-titian.

Titian, Venus with an Organist and Cupid. 1555. Museo del Prado, museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/venus-with-an-organist-and-cupid/b36421df-4d51-43b6-911c-c0517377e48d.

Article written by Ande Thomas

Ande loves the intersection of sci-fi and horror, where our understanding of the natural world clashes with our fear of the new and unknown. He writes about monsters and foreign horror and can also be found over on Letterboxd.

![Shudder Original: Frewaka (2025) [Movie Review]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1745585803192-XNB8A5ZAFGMPUQLTTBYR/frewaka.jpg)

Bones and roots adorn the walls of their dimly lit home. A mjölnir necklace hangs around K.’s neck as he hand carves incense into a small cauldron burner and a breathy soundtrack begins to play. This is a couple that is in tune—with themselves, with the natural world, and, as we will soon see, the supernatural world, as well.