The Influence of WWI on Horror: An Interview with Historian W. Scott Poole

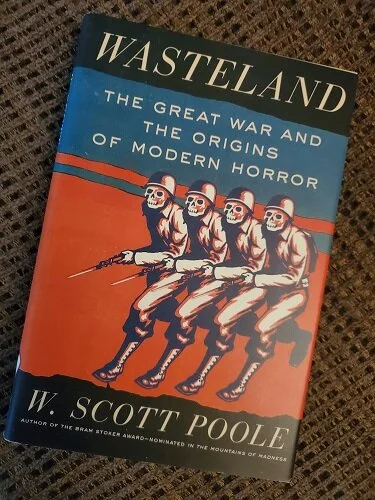

Both Halloween and Veteran’s Day have come and gone, but around the end of October, I found myself thinking about the role of war in horror, and that meant revisiting W. Scott Poole’s wonderful book, Wasteland: The Great War and the Origins of Modern Horror.

In Wasteland, Poole traces the influence of World War I on horror, in turn arguing that this catastrophic series of events also resulted in the development of the horror film. Visionary director James Whale, responsible for Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, is among those named who served in the war. This further prompted my own interest in speaking with Poole about the intersection of the Great War and the classic Universal monster movies we’ve come to know and love so much.

Poole, a professor of history at the College of Charleston, writes on horror, with his collection of public works including: Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting and Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror. Wasteland was originally released in 2018 to mark the 100-year anniversary of the ending of the Great War.

Early in Wasteland, you detail this romantic cultural narrative about going off to war—like this sense of adventure where everyone thought they would return home a hero. Obviously that didn’t happen. This seems to ring eerily similar to the “final girl” concept in horror. Do you think this attitude has become a cornerstone of horror, especially in those early movies?

There was a lot of talk in the summer of 1914 about war fever, and it did feel like everyone was joining up and that sort of thing, though that wasn’t quite true. A lot of people did sign up rather quickly. I was just actually reading earlier today about Bela Lugosi, about his decision to join up with the Austro-Hungarian Army, even though he had actually received a deferment as an actor. He had decided to join anyway.

I think at the very least there is a sense in the horror films that mostly veterans write, direct, and design the sets, for in the years from the 1920s on into the '30s, there is almost a sort of a nervous sense of expectation and the darker side of that, of doom. One of the ways that the Great War that made horror films—let alone the world we live in—there is the sense that the pulse of history is picking up in the same kind of way we anxiously glance at our news feeds. They—every day—very anxiously glanced at the newspaper. The sense that something bad is right around the corner very much comes out of the experience of the Great War. I think this is true for civilians as well as veterans. So many veterans are making the films, and writing the literature. [...] There’s that sense of horrifying expectancy, there’s that sense that something bad is right around the corner.

A point you made early in Wasteland, in the introduction, made me think of the development of monsters, especially during this early age of cinema. You point out the development of the gas mask during this period—this kind of vital piece of equipment that is engineered to save lives but also really visually robs us of the most human aspect of ourselves. Do you think this has had any impact on how monsters were rendered in movies? I’m thinking of Boris Karloff’s face and makeup in Frankenstein.

It’s absolutely true. One of the things I actually do in my classes on the Great War and horror, I bring in an actual antique gas mask and just let students look at it and tell me what they think. Inevitably, their response is [to call it] inhuman, industrial and frighteningly insectoid, but also organic at the same time. As you noted, it sort of robs the human face of what our basic expectations are for anyone we encounter. It’s more than a mask. … The nature of its design, it’s what the French surrealists ... called “the totem of the 20th century.”

You have a WWI veteran like James Whale, a lieutenant in the British Army. ... You know we know from his own notes on scripts, descriptions of people on set with him, that he played some role in almost every aspect in the design and mise en scène of Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein.

I actually might get in trouble for saying this—though I do note it in Wasteland, and certainly I don’t discount Jack Pierce because he was a legendary makeup artist for Universal in his creation of the monster—in Whale’s fascination with the gas mask, he paid very, very close attention so that he almost became his own cinematographer and set designer, I think he is very important in thinking about the look of Frankenstein. I think you see this in other figures influenced by German post-War cinema. …

My students frequently point out to me how often the gas mask continues to be an element in horror. It plays a very important role in the Purge series, in American Horror Story. It played an important role in the classic slasher My Bloody Valentine. It’s just showed over and over again. It even appears in the AMC series NOS4A2. … It seems every semester, a student finds another one.

With so many exposed to a number of human corpses during WWI, how would you say this has manifested in the early days vs. now? I think there’s an interesting contrast to be seen here like in early depictions of bodies in movies, versus what we see in Saw, for example.

Just a couple of thoughts about that. On the one hand … there was always, in the Universal pictures, a much gorier subtext than is immediately apparent. I would not downplay the role served by the display of dead bodies. Very strange movies, like Bela Lugosi in Boris Karloff’s The Black Cat in 1934, that actually includes seeing where Lugosi’s going to flay Karloff alive.

That’s present. There may not have been the same special effects, but I don’t know that in the '20s and '30s they were any less shocked, so there is that element. But then I also think you’re absolutely right, In the post invasion of Iraq and the invasion of Afghanistan there was … a fascination with the display of the body in torment. I think that that is something that has come around again and is a way in American culture—in things what we call torture porn, gore porn—that it’s almost this chill on the back of our necks that we’re aware that there is a war that has been going on so long that there are people fighting in it who were not born by Sept. 11, 2001. And yet you know we live in a nation where something like 0.4% of the population serves in the military, and only 8% or 9% of the population are themselves veterans. So the population is not directly affected by this, but somewhere in the background of their minds they know that it happened, so filmmakers like Roth and Wan and others have been able to tap into that, the same way filmmakers were in the '20s and '30s.

In your view, how have the Universal monster movies continued to influence horror? What about them makes them stand as such perennial figures in horror? They have definitely seemed to stand the test of time.

They have. I think part of that is the influence they continue to exert on adult horror fans who saw these films for the first time … on television when there were four channels in the '70s and '80s. There were also important films being made by George Romero and Wes Craven and John Carpenter, etc. … They had also watched those classic films. There is an element of nostalgia, but beyond that, there is also the continuing artistic influence. I’m constantly amazed at how—thinking the new horror, like Romero forward—we sort of keep returning to certain kinds of themes. Freddy Kreuger was and is a kind of mashup of Max Schreck’s Nosferatu and Bella Lugosi’s Dracula. …

I see it kind of everywhere and of course it’s not always successful. Like Tom Cruise’s The Mummy effort, there’s constant efforts to reboot these monsters. Even when it doesn’t go great, I think that they’re so much a part of our cultural DNA that it’s interesting when it feels. In Universal’s attempt to reboot The Mummy in 2017/18, in the effort to do that, it was in a way because they seem to have not to have decided to be faithful to the source material … Next year there’s going to be an effort to reboot The Invisible Man, which I’m interested to see but also scared but not in a good way. … I’m not actually a person who hates every remake and hates every reboot because that’s just part of the history of horror: It’s reimagining these monsters, so to me it’s always interesting no matter how it comes out. I think The Invisible Man reboot is the one I have the most mixed feelings about because I just it’s difficult for me to see how it’s going to go. We’ll wait and see.

I heard that Robert Eggers was doing the Nosferatu remake, and I’m really genuinely optimistic about that because I just saw The Lighthouse and I adored it. I saw The Witch and I adored that.

I think that Eggers is an interesting example with your question. If you haven’t seen it, in one of the latest issues of Fangoria, Eggers and Ari Aster have a great discussion about Frankenstein and the Bride of Frankenstein, which Eggers has mixed feelings about, as you recall. Ari Aster loves it. Their conversation was really interesting, and I guess this goes to your question about the influence on contemporary horror, because Eggers goes all the way back to Murnau. He lists Murnau, the director of Nosferatu, as one of his great influences. Frankenstein, especially the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein, Eggers names as too high camp for him. He thought the material was serious enough that it could bear more weight; I believe was the way he put it. And that made a lot of sense to me in terms of filmmaking styles because I can imagine—Hereditary and even more so Midsommar—both of them are incredibly over-the-top fantasy, even the auditory experience of them. And I think Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein was that for audiences; it was that level of emotional intensity. It was two different filmmakers responding to the classics in two very different ways.

I recall from a previous discussion that you have a particular fondness for director James Whale. How do you think Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein are distinct from the Universal monster corpus?

I think two things: one, nearly perfect design of both Karloff’s monster and Elsa Lanchester’s Bride, and I think that the images are so iconic and recognizable because it’s so simple but it’s also so good. It so well captures a very art deco, industrial plus organic monstrosity, that no one had ever seen anything like it before. I just think that Whale and Jack Pierce completely nailed that, so that’s the reason why, as I say in Wasteland, that the image of Frankenstein has been used for everything from hamburgers to cereal. It’s just kind of instantly recognizable. The second thing is, I think that Whale did something that is very difficult to do … that is to strike a balance between the monster being both completely terrifying and utterly sympathetic. …

I think another brilliant film that matches this is The Babadook, where there is both terror and sympathy. But it’s very, very hard to do, but James Whale was able to do it.

Following on this, in summary, how do you think the experiences of those who served in WWI shaped the early days of horror in cinema? Do we still see these influences today?

I think it’s difficult to imagine Universal taking on the number of classic monsters without a number of European emigres that start coming in the late '20s. … Bela Lugosi, who had served in the Austro-Hungarian army, playing Dracula; James Whale, responsible not just for Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, but also The Old Dark House, which also set the paradigm for the haunted house film. But also the making of The Invisible Man.

It would have looked different had it been different. It really is Great War veterans and emigres from Europe that really become the bridge for horror to come to the United States, primarily through Universal Studios and that was not an easy process. Americans were simply not that interested in horror before the 1920s and '30s. If you had a haunted house film, and there certainly were plenty of those, it always made for laughs. A lot of physical humor. It always starred someone like Buster Keaton and then there’s this Scooby Doo ending where the ghost turns out to not actually be a ghost.

Americans just weren’t that interested. They talked about films that we call horror films as “weird” films, and “weird” meant both having horrific elements and also being outside the United States. These emigres coming to Universal and to Hollywood and working Laemmle elder and junior, they really create the idea of horror in America.

I’ve previously read (in Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror by Michael Mallory) that the sets in the Universal movies were largely Expressionist. Thinking specifically on Frankenstein, is this kind of design choice reflective of the real horror faced in the war?

When you watch these films—the Bride of Frankenstein is a good example, but there’s also so many others—you get the sense that you’re watching a dream, a nightmare. There’s a hallucinatory element to it, and I think for many, certainly for James Whale, that was an experience that soldiers in the Great War called battle hypnosis—this state, under the terrible conditions of the trenches, sleeplessness, the anxiety that accompanies all of it, one simply sees things, as we know from the 1980s definition of post traumatic stress disorder, that are not there. One has hallucinatory experiences. …

Murnau, himself a veteran, used this in Nosferatu, in Faust, in really all of his films. It certainly plays a role in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which was written by a Czech veteran of the Great War. And Whale, a veteran himself, also had the experience of the trenches and was also watching these films.

One bit we know about Whale was that during the making of Frankenstein, in the studios at Universal, he insisted on watching over and over again The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and on the other hand, you also had Great War veteran Fritz Lang with Metropolis.

The visual experience is communicated in two ways. There is the actual personal experience of combat and it communicated that to the 1930s and '40s generation of filmmakers. I would also note that a film that seems pretty far afield and that doesn’t get a lot of love, the 1939 Son of Frankenstein, when you give it a sympathetic rewatch, it’s better than you remember it. It actually depends very much on the style of the German expressionist era.

In the wake of the Great War, especially with so much upheaval, was there a change in how gender was portrayed in horror? (Here I’m thinking specifically of The Old Dark House. Though not technically one of the classic monster movies, how women are written and portrayed in this movie is a dynamic, witty and rather fun a lot of the time, for example.)

When I watch with groups or with students films like Nosferatu, they are often quite surprised at the character of Ellen. She becomes almost a protagonist of the film. She is in some sense Nosferatu’s final girl, in that she is the monster fighter and killer. She destroys the vampire. Her husband Hutter and Professor Bulwer are passive, ineffectual and generally useless. She takes it upon herself. I think your example of The Old Dark House is wonderful because the female characters are not passively screaming their way through the film. The character of Rebecca Femm is also really wonderful.

I think a lot of these films played with concepts of gender; this is especially true in Bride of Frankenstein. They played with gender in unexpected ways for the time, and I think that has something to do with the fact that the 1920s and '30s were really quite revolutionary when it came to reimagining gender. So there’s that kind of forgotten world of that period.

The other thing is, if you looked at movies across the board in the '20s and '30s, the women in these films are much stronger than they are in Hollywood productions of the '50s and '60s. Characters played by silent film actors like Claire Beau or May West, who made her way into the talkies, and Joan Crawford, they often played very powerful figures. Then we kind of have what has been called the “domestic revival,” the revival of allegedly traditional gender roles in America after WWII. You have women being portrayed very passively and not being given top billing the way they were in the '20s and '30s. Interestingly, you have some of the very powerful women actors of the '20s and '30s, like Crawford and Davis, playing these kind of insane monstrous figures in a string of films in the '50s and '60s.

So it’s horror films, but also the way Hollywood and culture changes after WWII.

Looking ahead, do you think we’re currently experiencing a third golden age of horror? (I ask this based on the assumption that the Universal monsters were the first and the age of Romero/Carpenter/Craven was the second, as proposed in Dark Directions: Romero, Craven, Carpenter, and the Modern Horror Film by Kendall Phillips.)

What I’ll say about that is one of the film scholars I respect the most, a fellow by the name of Kendall Phillips, who wrote a wonderful book called Dark Directions, recent published a book called A Place of Darkness: The Rhetoric of Horror in Early American Cinema, that is about silent-era American horror. He essentially says that this is the third golden age. I understand that in a couple of senses.

On the one hand, we have horror films that are so aesthetically good, that they really go beyond the conventions of the genre and are enjoyed by people who would not describe themselves as horror fans. This reminds me of that moment in America in the '30s where it was asked, “Well how can a horror movie be good?” But then along comes Bride of Frankenstein and critics were sort of baffled as to what Whale could do. And this was much the same when George Romero finally gets his due into the '70s and into the '80s and '90s. Critics are starting to catch up.

I think we’re seeing some of that with the Jordan Peeles, the Ari Asters, the Robert Eggers. … Maybe we know we’re in third golden age of horror because we have these little clickbaity articles that keep popping up, saying things like “Get Out was not really horror” or “Midsommar was not really horror” or “The Lighthouse was not really horror.”

What they seem to be saying is the same thing people said about, for example, The Silence of the Lambs. It’s not a horror film because it’s too good. …

As a historian, my sense of it is always give it some time. Kendall Phillips said so, and to me he’s the authority on a lot of these things. … I guess I’m giving you a firm “maybe.” Let’s talk about it in 20 years.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Article Written by Laura Kemmerer

Laura tuned into horror with an interest in what these movies and books can tell us about ourselves and what societies fear. She is most interested in horror focused around the supernatural, folklore, the occult, Gothic themes, haunted media, landscape as a character, and hauntology (focusing on lost or broken futures).

Throughout the decades, slasher film villains have had their fair share of bizarre motivations for committing violence. In Jamie Langlands’s The R.I.P Man, killer Alden Pick gathers the teeth of his victims to put in his own toothless mouth in deference to an obscure medieval Italian clan of misfits.