Private Traps: Transphobia, Psychosis, and Grief in ‘Psycho’

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is a 1960 horror film that utilizes narratives of the transphobic moral panic of the 20th century, such as the case of Ed Gein, to depict the fictional murderer Norman Bates who is driven to psychotic, incestuous grief by the death of his mother. This grief drives him to dress as, and in his mind, become his mother, and kill people who threaten to shatter that illusion. As other scholars have described, these transphobic depictions—fusing violence with gender transition—have been incredibly harmful and damaging to transgender people. However, building on Sarah Ahmed’s conception of queer grief, along with Misha Crafts’ analysis of trans horror, I posit that a trans viewing of Psycho can reveal useful, albeit complicated, ways to consider trans grief.

Transphobic and Ableist Histories

In the early 20th century, similarly to now, there were many instances of sensationalizing the danger and alleged mental instability of trans people in popular newspapers and other publications (Cartwright 98-99; Velocci “Denaturing Cisness”). These stories were formed by and also shaped the fears of trans people. Beans Velocci, in “Standards of Care,” writes about how fears of trans regret have always shaped trans medical care. Early cis medical providers selected or rejected patients with the constant expectation that trans people would become violent after surgery and hormone treatment. “The question for Benjamin and Belt was not whether someone was really a woman but if they could pass as a woman, nor if they were really trans but if they would regret transitioning” (Velocci 463). This fear has continued to shape trans medical care, and now, political agendas, such as recent presidential executive orders seeking to ban trans children (and some adults) from medical care, criminalizing the support of trans children, and otherwise pushing trans people out of public life. Trans people, since the invention of the medical term “transsexual,” have been associated with mental instability and violence (Cartwright; Velocci; Kunzel). In addition to Dr. Harry Benjamin’s “standards of care,” horror movies and popular media have also promoted fears of violent, mentally unstable trans people.

Psycho was directly inspired by the story of Ed Gein (Encyclopædia Britannica). Ryan Lee Cartwright analyzes the narrative of Ed Gein, writing about the differing constructions of Gein’s pathology in local versus metropolitan newspapers, how these constructions were racialized, and how they were also constructed from the newspaper to the judicial level. Cartwright notes, “Before Gein was questioned, his police interrogators had already formed a lay theory of the gender and mental pathologies that they imagined to explain his macabre violence” which they suggested to Gein (104). Cartwright emphasizes that there is no clear connection between Gein and gender difference. However, this connection—transness and psychotic violence—was sensationalized through the national press and repeated by police and judicial authorities, as well as by Psycho.

This logic operates on two assumptions: that trans people are inherently mentally ill, and that mentally ill people are inherently violent. “When the metropolitan press identified Gein as a ‘psychopath’ and ‘transvestite,’ they sensationalized mental disability and gender dysphoria, fusing the two together” (Cartwright 100). Cartwright is careful to analyze how trans scholars and activists, in their desire to separate transness from psychosis and pathology, often reify the idea that psychosis is inherently violent. Trans disability scholars, such as Cameron Awkward-Rich, Eli Clare, Lucas Crawford, A.J. Lewis, and Regina Kunzel have written about the friction between trans activist scholarship and Mad Studies, a field of Disability Studies that focuses on “madness” including psychosis, reminding us that trans communities are not monolithic. What morality do we attribute to health and sickness? “Sickness” and “madness,” Awkward-Rich notes, are gendered and racialized. By moving toward normativity—away from “madness”—who among us do we disavow?

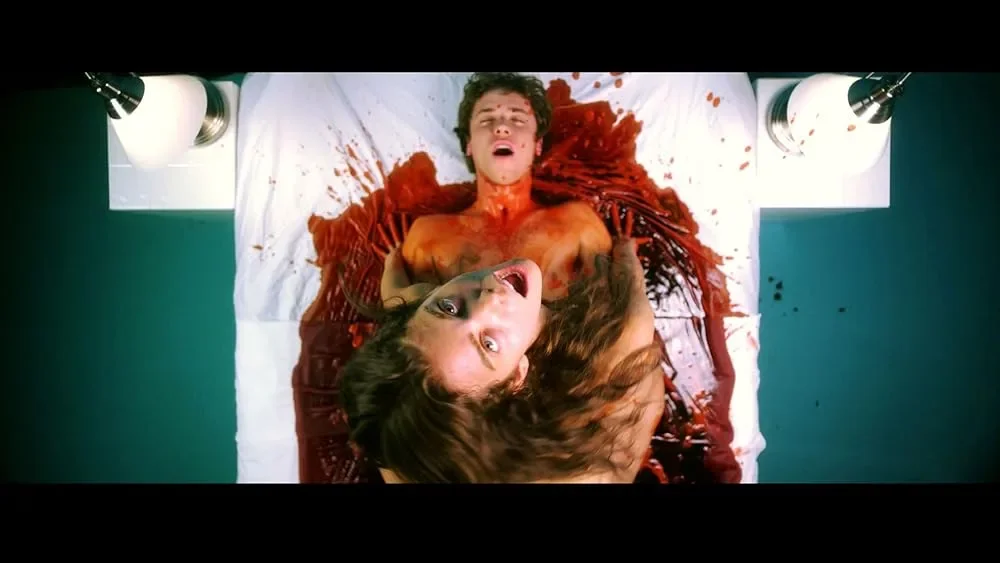

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), image via IMDB

Psycho may help us think through these questions. While Norman is not explicitly called transgender, the film uses transphobic images meant to evoke trans femininity. Historically, divisions between transgender people and “cross-dressers” have been fraught. Within queer communities, there has been intense difference—with cross-dressers or drag queens being socially revered, and transgender women being reviled—as well as slippage between these identities (Gill-Peterson). Of course, from the outside, as we see in contemporary times with drag bans as well as transphobia, bigots tend to conflate these identities. We see that in this depiction of Norman. His wig, as described in the working script on page 125, is “a mockery of a woman’s hair.” He is always described as a bad imitation of a woman, literally “mocking” cisgender women with his existence.

Other characters at the end of the film describe him as “a transvestite” (a common conflation of cross-dressing and transgender identity, particularly in the 1960s) to which the psychiatrist, the safe medical authority, states: “Not exactly. A man who dresses in women’s clothing in order to achieve a sexual change … or satisfaction … is a transvestite.” (Stefano 130). Here we see that very conflation: “a sexual change,” i.e. to change sex, is conflated with “sexual satisfaction” or kink. Norman is “not exactly” a trans person, but even in this half-hearted separation, he is still configured close to transness. “Not exactly” implies that he is, just, you know, a little bit different because his change has been brought about by collapsing the differences between the grieved subject (his mother) and grieving subject (himself). This psychiatrist, and this film, see an incestuous, violent, mad, overlap of griever and grieved subject as equivalent to the madness of a trans person. This mad transness is meant to distance the viewer from Norman, to transform him from Marion’s sympathetic mirror to something “other.”

After all, Marion, too, experiences madness when she steals her employer’s money. The narrative punishes her for this, even as it asks: wouldn’t you? Her madness is understandable, if unacceptable, whereas Norman’s is positioned as neither acceptable nor understandable. Can we resist this separation, this reification of acceptability, in our reading of Psycho? Alongside psychiatric and newspaper misrepresentations of trans identity, Psycho (and horror films at large) has had a significant role in popularizing violent beliefs about disability and transgender people (Cartwright; Gardner and Maclay). The effect these films, and the messages in them, has on trans and disabled bodies cannot be understated. “These movies hurt me and I kept watching them, and there’s nothing redemptive about that. They were all I had” (Lisowski 48). Disability scholarship, including scholarship that overlaps with trans scholarship, tends to view horror movies through a negative lens (Cartwright 163-164). By contrast, queer studies has long embraced the radical potential of the horror movie, “theorizing a rich array of desires and identifications through which queer viewers can relate to horror monsters” (Cartwright 164). While Cartwright, and other scholars, are rightly suspicious of a totalitizing embrace of monstrosity, it is clear that horror movies are also a site of intense affects for transgender people. However, even these more complicated affects are still rife with negative feelings.

Psycho and Trans Grief

In “The Transsexual’s Guide to Horror Cinema,” Misha Crafts writes, “I felt compelled by, even obsessed with, the feeling horror movies gave me. This is interesting to me because there is an assumption among a certain kind of cultural critic (both conservative and liberal) that ‘we are what we eat’ politically speaking. I think this is true in some ways, but I would like to add to it that ‘we eat what we are.’” The emotions of fear and desire in horror can be particularly compelling for marginalized viewers. This is despite, or possible even because of, the role horror plays in marginalizing them. Trans people are formed through and by the transphobia we struggle against daily. Building on Tey Meadow’s work, Kadji Amin places disability frameworks and transness together, in a metaphor of “scar tissue” to argue that “[t]he way we express our [trans] genders bears the trace of the non-trans world’s genocidal effort to deny them” (41). We are made of this transphobic scar tissue. We are made of horror films. “We eat what we are.” To be trans is to be made to feel bad in your body and in the world, particularly right now.

Horror movies are part of this bad feeling. However, simply rejecting bad feelings is not useful—being forced to perform happiness under conditions of transphobia is another kind of silencing violence. Our acceptance being contingent on happiness—on the success of surgeries, on being palatable to medical and political gatekeepers—is, as Amin and Long Chu express, unacceptable. Additionally, normative assimilation is violence for those trans and cis who are unrecoverable to normative, white supremacist society, like the non-white subject, or the mad subject. When we feel repulsed by the Norman figure, trans people must contend with our own assimilative impulses without fully embracing the negative, violent stereotypes about transgender or mentally ill people. What kind of complicated bad feelings do we disown when we reject his mad, debilitating grief?

In many ways, Psycho is about grief. Sara Ahmed, writing about queer grief, voices the way that messy boundaries between the griever and the grieved indicate an ongoing relationship with the departed. Building off a queering of Freud’s theories of grief, she articulates a queer grief where the grieved subject becomes a permanent part of the griever. “One can let go of another as an outsider, but maintain one’s attachments, by keeping alive one’s impressions of the lost other” (160). The psychiatrist in Psycho links Norman’s gender deviancy to his grief, particularly, when grief threatens to overwhelm him: “And whenever reality came too close, when danger or desire threatened that illusion, he’d dress up, even to a cheap wig he bought, and he’d walk about the house, sit in her chair, speak in her voice…” (Stefano 130). Norman misses his mother so much that he becomes her. In a mirroring gesture, after Marion Crane’s murder, her sister Lila steps in to fill her role, flirting with her deceased sister’s lover. The grief in Psycho is not healthy. Both instances walk a line close to incest and sublimation of the grieved subject, a sublimation that threatens to overwrite and erase the reality of the persons lost—but it is ambiguous whether this erasure occurs. This sublimation also keeps the grieved subject alive, in a tenuous sense.

Anthony Perkins in Psycho, image via IMDB

Even when they are not with us anymore, the grieved subject still has influence over us, and will continue to have influence over us. When Amin and Meadows write about the social scar tissue that the gender of trans people are made out of, I think of the loss of my trans and queer friends, loved ones, and community members. I find use in thinking about how I will never “recover” or “get over” their deaths even as I continue to live. Their impression on me is ongoing, making up myself: It is inextricable from the scar tissue that forms my skin. This transphobic scar tissue that we live with is made up of the dead and wounded: my loved ones, myself.

Norman’s false cheer over his real grief, anger, and cacophony of violent emotions is compelling. The scene in which he and Marion discuss escape is almost hypnotic, demonstrating a real power: in Norman’s grief and in both of their various unfulfilled, unacceptable desires. While not equal, as Marion’s desire for her own life (and to have her lover) is sympathetic and Norman’s incestuous desire for his mother is not, the power and potential of catharsis in both are heady. In the script (page 123), Norman is directly compared to his stuffed birds, unable to fly away. This description contains the transphobic element of “falseness” or of a stuffed construction, as much as it also implies death and powerlessness. The expression of these unfulfilled desires alongside the powerlessness of each character is cathartic, giving a cinematic structure to feel grief, fear, and rage.

Rage is important. Rage, alongside grief, fuels Psycho. Rage drives Norman to kill, reifying the trans and mad connections with violence, while cinematically punishing Marion for her own sexual desires and transgression. However, it is, in some ugly, uncomfortable ways, cathartic. Rage also fuels Lila and Sam’s desire for justice, most visible in the scene where Sam confronts Norman. Originally written in the script to be “calm,” in the film, Sam’s barely contained fury as he backs Norman into his office creates an uncomfortable, deeply compelling scene. I am also debilitatingly, desperately furious—and confused—and baffled—and hurt—that trans grief goes unrecognized by others. Psycho’s emotions of grief, rage, and helplessness are familiar to me, as is the madness at the heart of Psycho. I am mad; I am furious; I feel as if I live in a different world than the people around me, a world of strange desires, transness, and compounding, heavy, wretched, unending grief. I feel for Norman Bates, and I feel for Marion Crane.

Part of this reading is asking the question: How can we take this use and create new films—and books, and comics, and other creative expressions of horror—that build on and perhaps re-signify the connections that Psycho makes for us? Or perhaps, can we feel for Marion and Norman at the same time? Crafts’ essay argues that horror movies that are truly transgressive can be read in ways that are helpful to trans people. However, this reading is an active choice the viewer must make. Sometimes this use requires a fracturing of a film: a pausing in moments that offer something of use, and perhaps, skipping, or erasing, other moments. This proposed use does not feel good.

Psycho is an ugly part of transgender history, a reflection of what non-trans people think about trans people, and it has played a material role in the violence that trans people face. Psycho is part of transgender scar tissue, a part of us that we did not choose. Perhaps because of this, there are parts of Psycho that feel uncomfortably close, and unexpectedly cathartic. Following Cartwright and Awkward-Rich, we should be careful about what norms we reify when we reject this ugly depiction. A complex trans reading of this film does not require an embrace of the horrifying myths and violent stereotypes of trans people, even as it must contend with them. A trans reading does allow us to question our own values, our assumptions about mental illness and psychosis, and our own desires for safety, as erroneously promised by normativity. Psycho can also give a cathartic structure to feel the kind of grief and rage we experience as trans people.

-

Ahmed, Sara. “Queer Feelings.” The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh University Press, 2004, pp. 144-167.

Amin, Kadji. “Trans Negative Affect.” The Routledge Companion to Gender and Affect, Routledge, 2022.

Awkward-Rich, Cameron. The Terrible We: Thinking With Trans Maladjustment. Duke University Press, 2022.

Cartwright, Ryan Lee. Peculiar Places: A Queer Crip History of White Rural Nonconformity. The University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Crafts, Misha. “A Transsexual’s Guide to Horror Cinema.” hypocritereader.com. July 2023. www.hypocritereader.com/101/a-transsexuals-guide-to-horror-cinema. Accessed January 1, 2025.

Gill-Peterson, Jules. “Queens of the Gay World.” A Short History of Transmisogyny, Verso, 2024.

Gardner, Caden Mark, and Willow Catelyn Maclay. Corpses, Fools and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema. Repeater, 2024.

Koch-Rein, Anson, Elahe Haschemi Yekani, and Jasper J. Verlinden. “Representing Trans: Visibility and Its Discontents.” European Journal of English Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2020.1730040.

Kunzel, Regina. "Queer History, Mad History, and the Politics of Health." American Quarterly, vol. 69 no. 2, 2017, pp. 315-319. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2017.0026.

Lewis, Abram J. ”I am 64 and Paul McCartney Doesn't Care.” Radical History Review, Issue 120, Fall 2014. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2703697.

Lisowski, Zefyr. “The Girl, the Well, the Ring.” It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror, edited by Joe Vallese. Feminist Press, 2022.

Psycho. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay by Joseph Stefano. Shamley Productions, distributed by Paramount Pictures, 1960.

“Psycho.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020.

Stefano, Joseph. Working script of Psycho. December 1, 1959. Horror Scripts and Ephemera Collection. SC.2019.04, Box 3, Folder 8. ULS Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Velocci, Beans. “Denaturing Cisness, or Towards Trans History as Method.” Feminism against Cisness, edited by Emma Heaney, 2024.

———. “Standards of Care.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, Volume 8, Number 4, November 2021. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-9311060.

Article by Dave V. Riser

Dave V. Riser (he/him) is a gender ghoul pursuing his PhD in English Literature. His research interests include horror fiction, queer and transgender studies, disability studies, and affect studies. He has a variety of short fiction, including “EACH-UISGE” in The Off Season: A Coastal Horror Anthology, as well as "Triage" in The Arkansas International. His nonfiction appears here, and in Bloodletter magazine.

![A Self in the Setting: Exploring Dracula’s Castle [video game horror]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1738798336699-OXLE0MWHEWE0DODVC10N/castlevania1997.png)

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”