Endless Summer Syndrome [Movie Review]

As any returning reader of WSB knows, we place a high value on the horror and thriller genres, but there are admittedly times when those genres aren’t enough to fully encapsulate “what sleeps beneath.” Take for instance Kaveh Daneshmand’s directorial debut, the French-language Endless Summer Syndrome, which bills itself as a family drama, but manages to embrace the dark secrets that run quietly beneath the surface.

Led by a phenomenal performance from Sophie Colon as Delphine, an attorney who one day gets an anonymous phone call from a co-worker of her husband Antoine’s (Mathéo Capelli) saying that, at a recent work party, he had drunkenly admitted to being involved in an affair with one of their adopted children. Nonplussed at the accusation, Delphine tries to get the caller to reveal their identity, insisting that they could just be some random psychopath trying to get a rise out of her and her husband. Nevertheless, the charge quickly takes hold in Delphine’s mind, as she begins second-guessing every interaction she sees Antoine have, particularly with their daughter, Adia (Frédérika Milano).

Almost from the start, the viewers can feel the coming pain, as the family basks in the final weeks of summer before their son Aslan (played by Gem Deger, who also co-wrote the film with Daneshmand and Laurine Bauby) flies to New York to start entomology school. When we are introduced to Delphine, a moderator is wrapping up remarks on a panel related to Delphine’s work on reforming French schools and the role they play in children’s rights. “Family is the first place where a child learns about violence,” she interjects, “I know that the value of one’s life … is something you have to learn at home first.” Unbeknownst to Delphine, her own words will soon take on more significance.

Family Horror

The introduction to the rest of the family isn’t nearly as foreboding. As they lounge around the pool, or as Aslan instructs Adia on how to properly care for his pet snails while he’s gone, they come across as a remarkably open, well-adjusted family. The kids seem happy and at ease with both of their parents and with each other—Aslan seems genuinely hurt when Adia tells him she has plans with a friend on the night before he leaves, and Delphine makes the family cocktails as Antoine and Aslan play Scrabble and work on Aslan’s French accent. It’s a picturesque scene that makes you almost wish that Delphine didn’t hear her phone ringing from inside the house just after sitting down poolside.

On her return to the pool though, Delphine glances over at Adia sunbathing topless, and contemplates the scene before approaching her daughter, tidying the towels and casually suggesting that Adia might be getting a sun rash and should maybe put a T-shirt on. It’s the first scene that really jarred me out of my American sensibilities and, because it’s a film that promises a challenging look at complex moralities from the start, sent me deep into the hallowed annals of Reddit to find out just how common it is for teenage girls to go topless in front of their parents in Europe. It’s not, it turns out, but nor is it completely unheard of, although nudism in general is on a steady decline among young people. Still, it’s an effective early scene that serves to upend audiences, who can’t help but feel their expectations being tossed out the window as they reappraise the powers at play.

In a bit of clever writing, Delphine begins her investigation by finding Aslan in his bedroom as he tends to his snails. Aslan is smoking a joint and, to his surprise, Del joins him. When she starts to press him on his sister’s love life, Aslan replies, “Um, does the joint make you, uh, paranoid?” Indeed, it’s after this scene that we begin to see the film’s events through Delphine’s eyes, softly blurring the lines of objective reality. The effect is never psychedelic or fantastical—it’s just enough to stand in for our own shifting understandings that have already been primed for arousal.

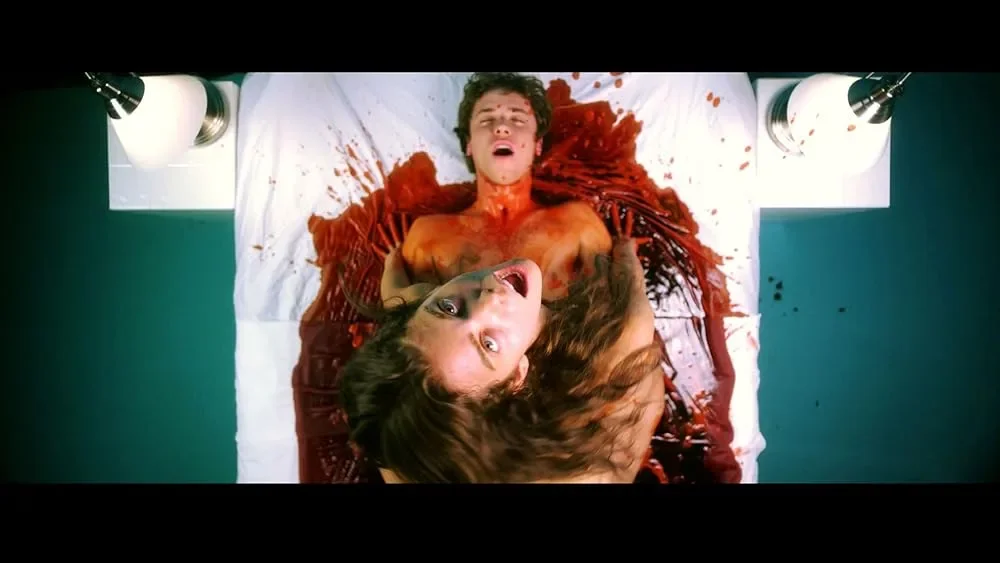

Image via Altered Innocence

Suddenly, every interaction between Antoine and his kids (especially Adia) is seen by Delphine as potentially insidious. When she catches him treating a burn on Adia’s leg in the kitchen, she snaps that he’s doing it wrong and whisks her off to the bathroom to do it herself—safe, she imagines, from his lustful touch. There, she grills Adia on her sex life, admitting that she’d found condoms hidden in her room. This invasion of privacy is the first of several open acts of betrayal by Delphine in her increasingly desperate attempt to get to the heart of the threat that is slowly eating at her family from the inside out. What’s more, when the affair is finally discovered, even then, the film’s revelations are not finished—a fact that, unfortunately, is robbed of its gravity because so much of the tension the film spent its energy building in the first half is released by Delphine's discovery.

Endless Summer Syndrome layers questions of morality so thickly, it’s difficult to tug on a single thread without knotting up another. Questions about consent, about power dynamics in sexual relationships, about family politics—all are woven tightly into the tapestry of the film and Daneshmand doesn’t feel eager to offer any help in answering any of them. It’s impossible to come away with the impression that Antoine is innocent, or worse, a victim, but the film sits comfortably in a gray area allowing audiences to look more closely at each of the characters separately and in relation to each other, emphasizing the effects on the family, rather than focusing on a victim-perpetrator relationship.

While I do view that as a positive, I couldn't hold it against anyone for feeling like it muddies the message. With such sensitive topics as these, there will rightly be those who feel the film ought to take a formal position, one way or another. I don't, however, feel like its refusal to make an explicit statement can be misconstrued as a tacit approval of Antoine's or anyone else's actions in the film, instead forcing the viewers into the uncomfortable position of confronting questions that we've considered settled since long before we've had to consider them at all.

Despite a couple of shortcomings in its structure and storytelling, Endless Summer Syndrome is a methodically provocative title that confidently pushes past most audience's comfort zones. It's a fitting punctuation mark on the 2024 catalog of distributor Altered Innocence (Knife+Heart, The People's Joker), which focuses on edgy and alternative queer coming-of-age stories.

Endless Summer Syndrome is available on digital services now, and you can support WSB by making your purchase of Endless Summer Syndrome and other films on physical media through our affiliate link at Movies Unlimited.

Article by Ande Thomas

Ande loves the intersection of sci-fi and horror, where our understanding of the natural world clashes with our fear of the new and unknown. He is an independent member of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies and a supporting member of the Horror Writers Association. He writes about monsters and foreign horror and can also be found over on Letterboxd.

![[Movie Review] Dead Mail (2024)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/1745079293263-SFBEIPQXTRG91EFCVDA4/Screenshot+2025-04-19+at+12.14.27%E2%80%AFPM.png)

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”